Evrychou — until recently a little-known corner at the foot of Mount Troodos, where little more than 900 people now live — grabs your attention at first glance, as soon as you arrive after turning off the worn-out Nicosia – Troodos highway. The village is 50 km south-east of the capital and 30 km from the Troodos range, lying 440 m above sea level, on the eastern bank of the River Karkotis.

You’ll always find a reason to visit here, especially after the opening of the Museum in honour of the railway which once existed in Cyprus.

We came here in September, soon after the official opening of the Museum: in a painstakingly restored colonial railway station, spread out over two floors.

From 14th June 1915 right until 31st December 1931, Evrychou was the Western terminus of the Cyprus Government Railway (CGR). Later, the five miles of railway track in this location was practically left abandoned.

In the Museum

For Reference: In subsequent years, the station building was used as a sanitary-technical centre and afterwards a guest-house for forestry workers. Relatively recently, the station and its surroundings were reconstructed to create the Cyprus Railway Museum. Works in the renovated building took place from 2010-2012, after which an open hangar was built to store a mail wagon and draisine. The first exhibition appeared on display in November 2014 and on 9th September 2016, the Museum was fully opened to visitors.

The premises surrounding the Museum were tidied and kitted out with the necessary facilities. A magnificent flowerbed of fragrant, luxurious roses (in addition to the beauty of their inflorescence, the rose bushes on Mount Troodos often reach incredible heights — more than 2 metres) was planted around the vicinity. This plateau reveals a scenic view of the surrounding green expanse and the Troodos foothills.

Please Note: A preserved fragment of the railway track (a narrow-gauge railway with a 600-1200 mm track width, thanks to the smaller size of the trains, which allowed for economising on operation costs) provides the finishing touch to help immerse you in the historical past of Cyprus. A traditional red postbox from the UK further complements this (after the departure of the English, independent Cyprus has continued to use these boxes, now with the compulsory yellow colour and the Cypriot emblem, to collect mail from city houses). That said, the main attraction — one of the very mail carriages which used to operate here — sits under a light, modern-style, open hangar. But we shall leave that “for dessert”.

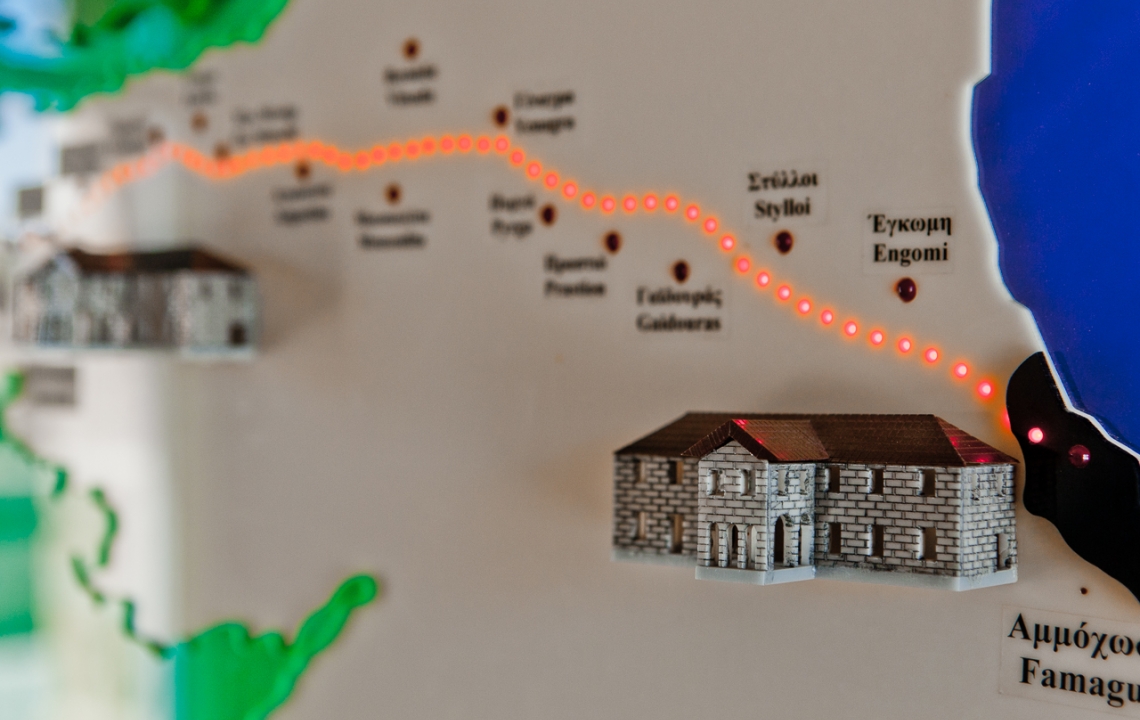

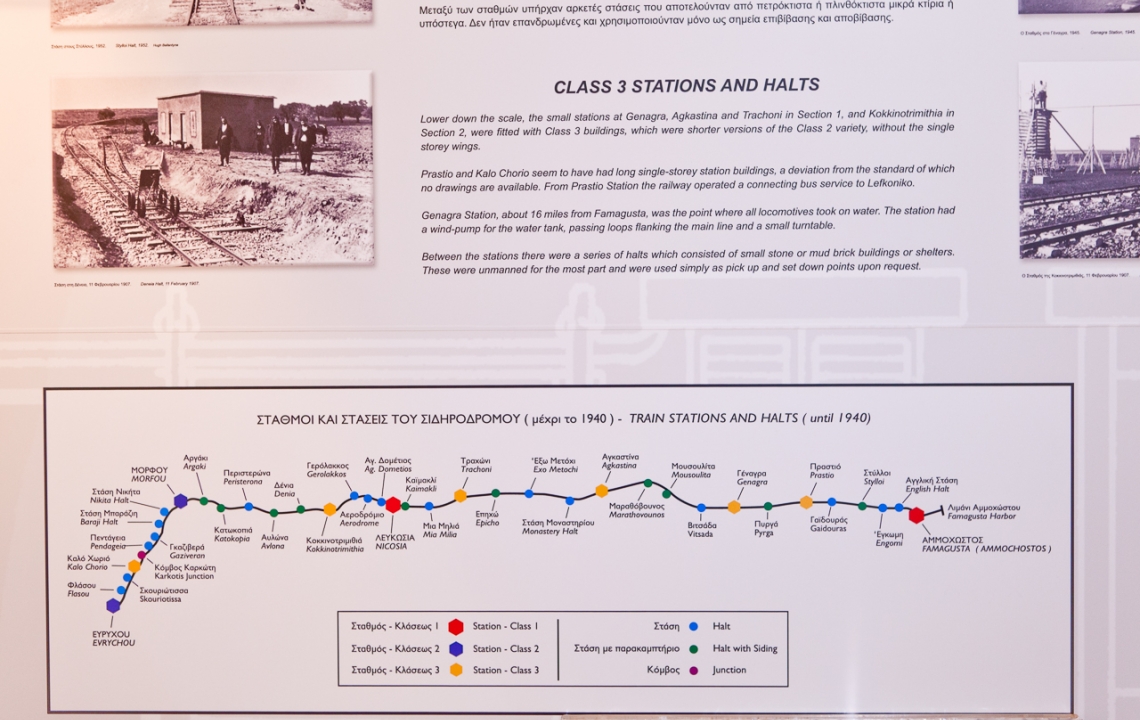

As you enter the building, you’re immediately able to familiarise yourself with the only CGR (1905-1951) line which existed, along with the route it used to take. The train would go from Famagusta — through Kythrea and other villages (now the territory of the part of Cyprus occupied by Turkey) to Nicosia; through Kokkinotrimithia and Avlon to Morphou — and finally, to Evrychou. In front of you stands an interactive map of Cyprus in two languages (temporarily, according to the Museum curator): Greek and English. If you don’t know either language, however, you'll still be able to understand everything, as the material is provided in a simple and very visual format.

And so, the inauguration of the railway took place on 21st October 1905, in the presence of the consul, Sir Charles Anthony King-Harman. There were only 39 stations opened on the island, with the track extending a total of 122 km. A journey to the terminus took close to 3 hours.

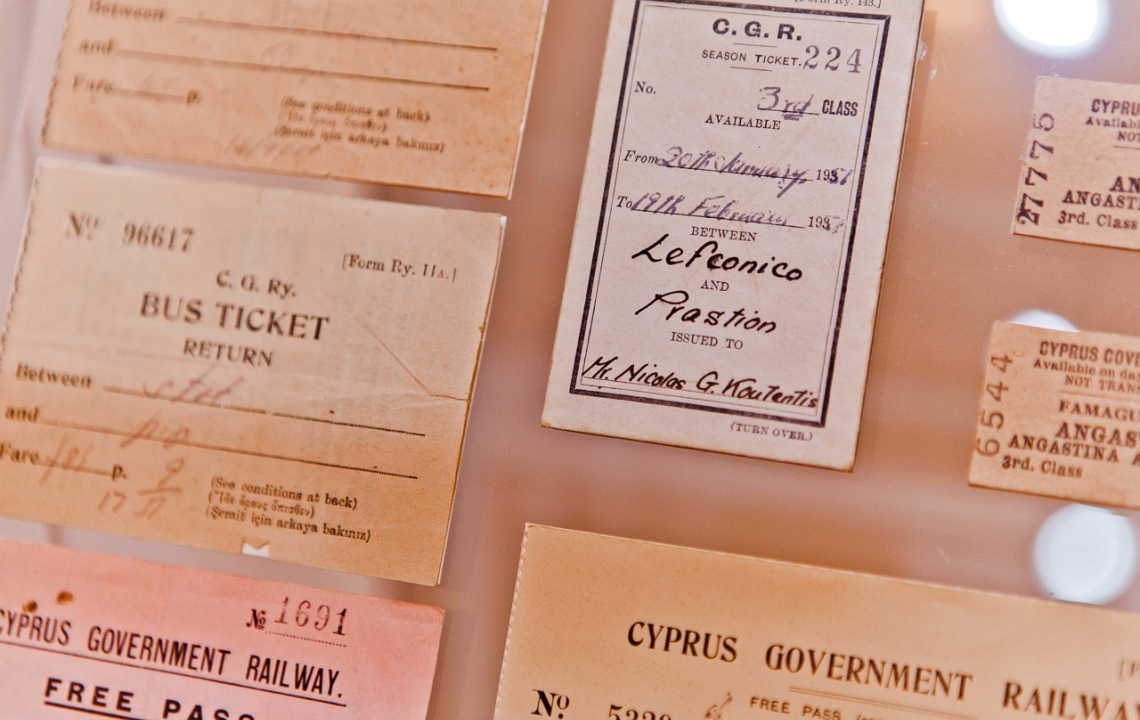

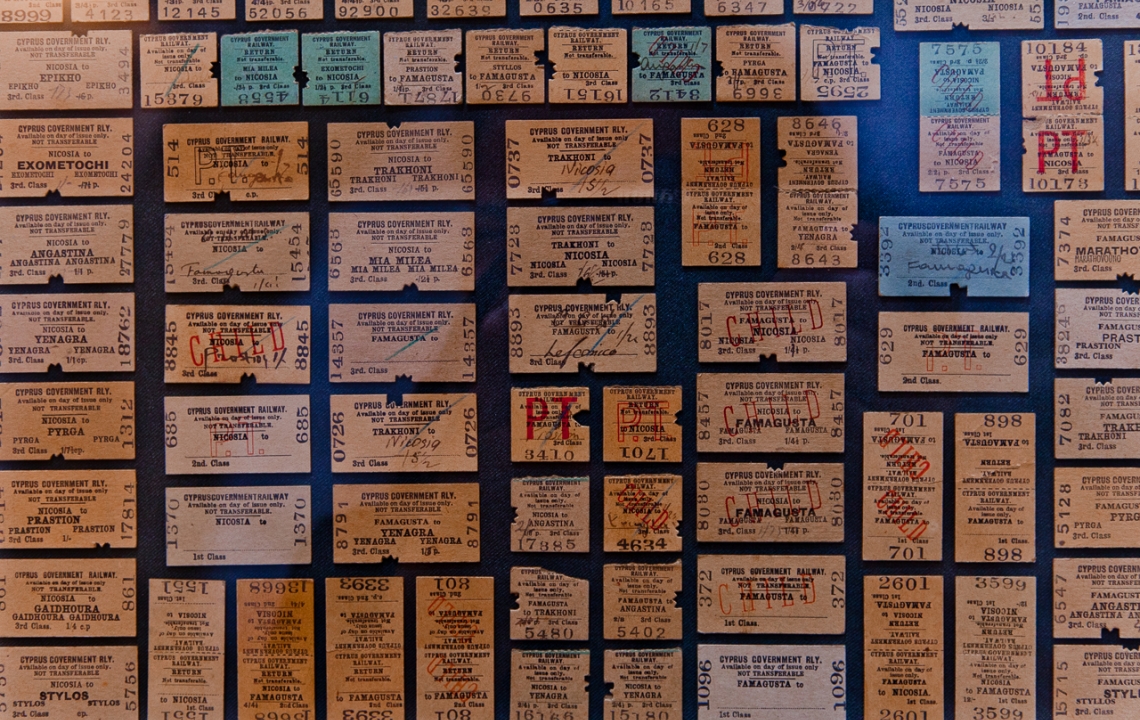

For those interested: the cost of a ticket from Nicosia to Famagusta, with all its route stops included (roughly a two-hour journey), totalled from 3 to 6 pence. The most impatient passengers, who would often complain about how slowly their trains moved, were able to alight and walk alongside the carriages. Once the passengers had grown tired, they would then reenter and rest inside their cabins, which we can see in photographs from those years.

Passenger trains would make two trips per day, while another would be “added” on Sunday daytimes for those working in Nicosia, who wished to wind down on the island’s best beaches.

The main issue for the island railway was notably posed by its local rivers: in summer, as is well-known, they would dry up and become shallow, whereas the flash floods in winter were genuinely capable of tearing down and washing away everything in their path.

You can see stands on the walls which more extensively describe the chronological turn of events enveloping the period from 1878-1972.

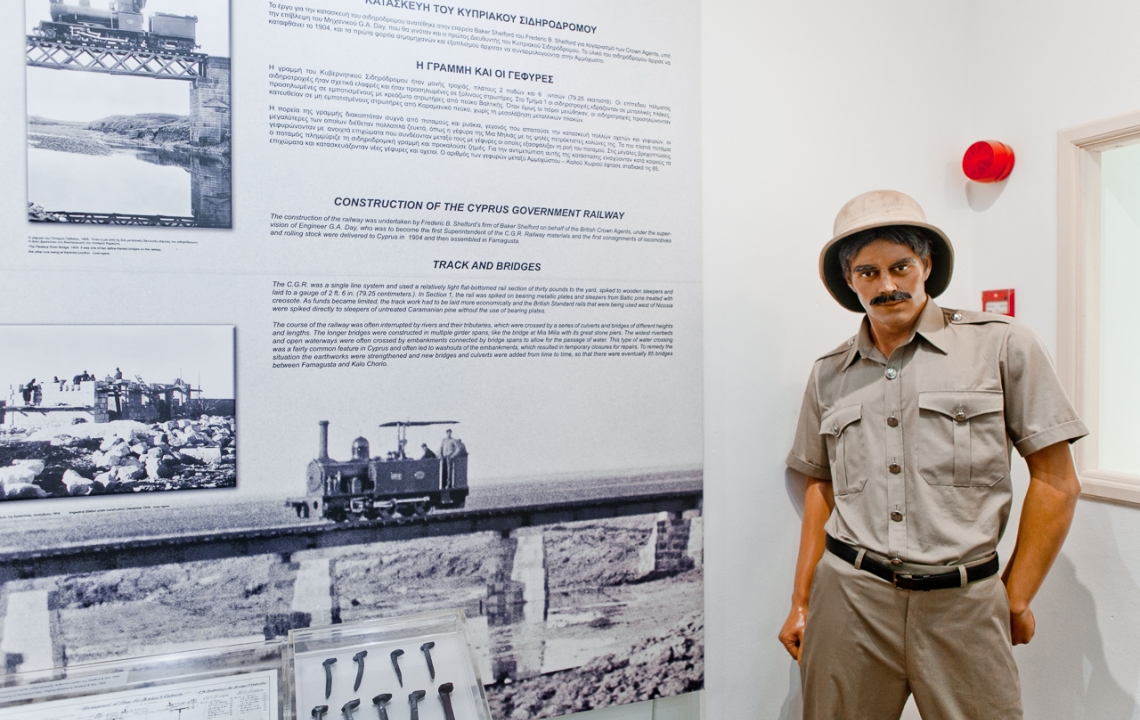

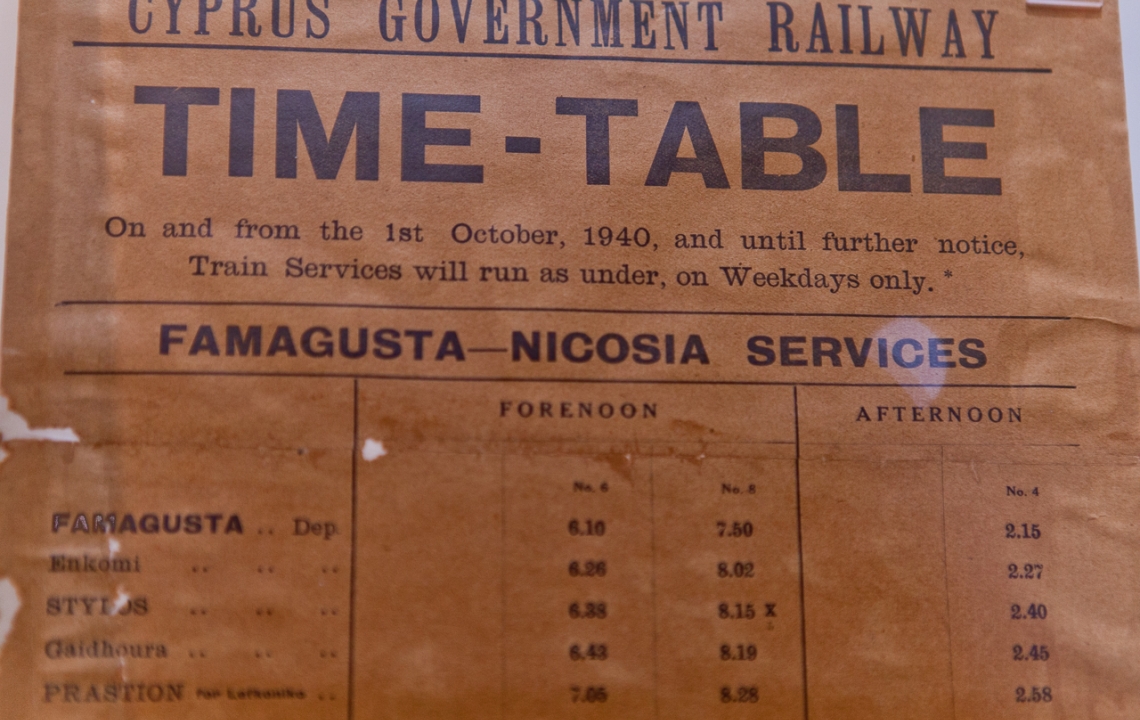

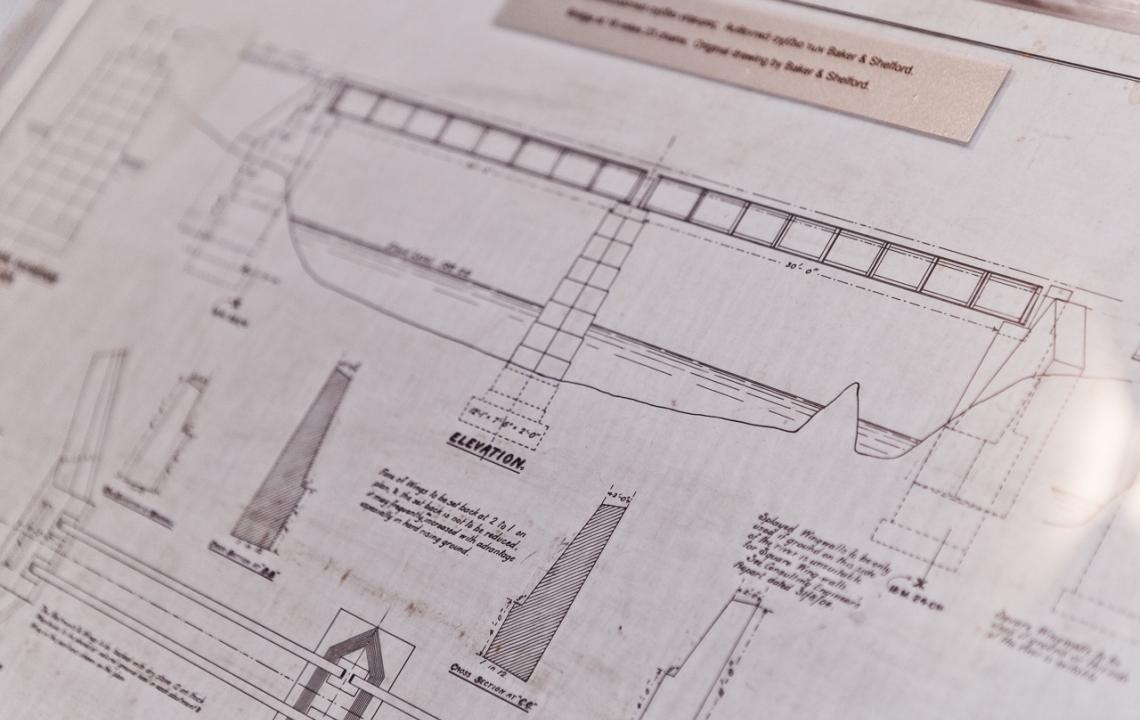

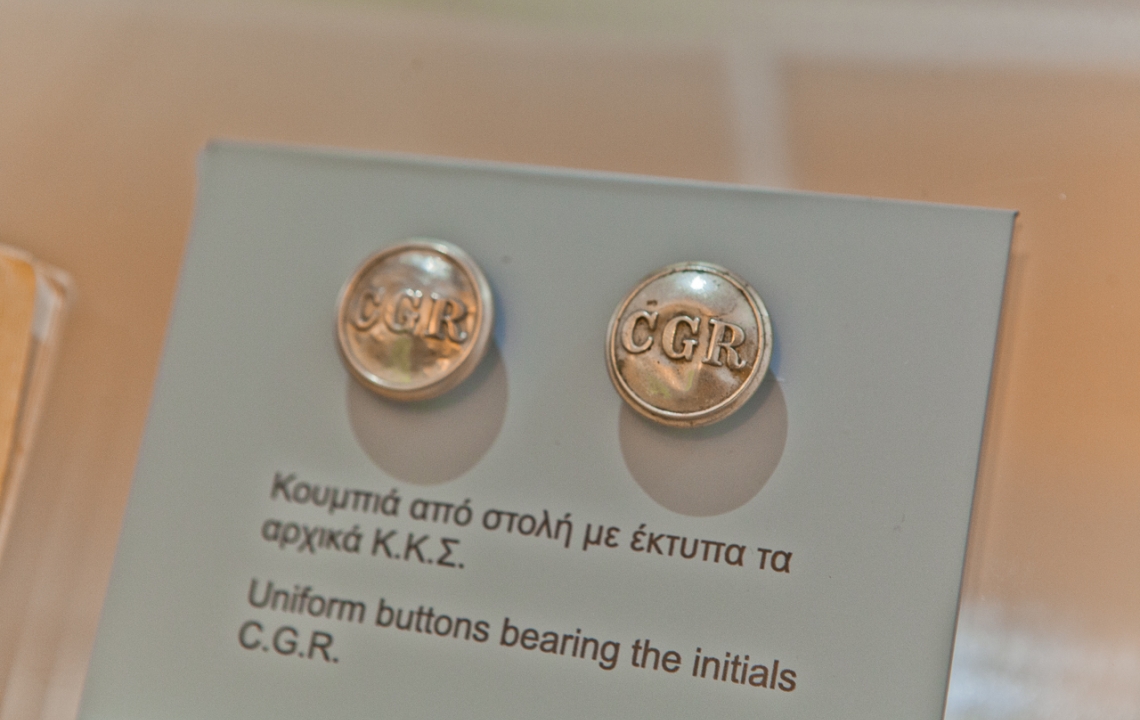

The former station halls have been filled with stands featuring photographs and sketches, as well as a detailed image of the route from Evrychou to Famagusta, in an aid to improve the visual experience. The stands also display elaborate models of the station and locomotives (steam engines), as well as carriages with figurines of passengers inside. Besides this, there are mannequins dressed in uniforms and display cases with a collection of knick-knacks relating to this significant chapter in the history of Cyprus: tickets and timetables, fragments from carriage designs, lights, plaques from different years — this will be moving for everyone, both children and adults.

The exhibit observes a chronological system: not only are the images of the stations and the characteristics of the machinery shown for every decade, but a historical canvas is created and is this is by no accident; after all, the first half of the 20th century, as we all know, had an abundance of social upheavals and wars. A site as strategic as a railway station and the ability to communicate through it, albeit on the island, could not remain out of the action, but we shall discuss this a little later.

As you can observe, many of the exhibits on display were given to the Museum as gifts from private individuals, the majority of whom were Brits. The main benefactors were K.E Rook and T.H. Bagley.

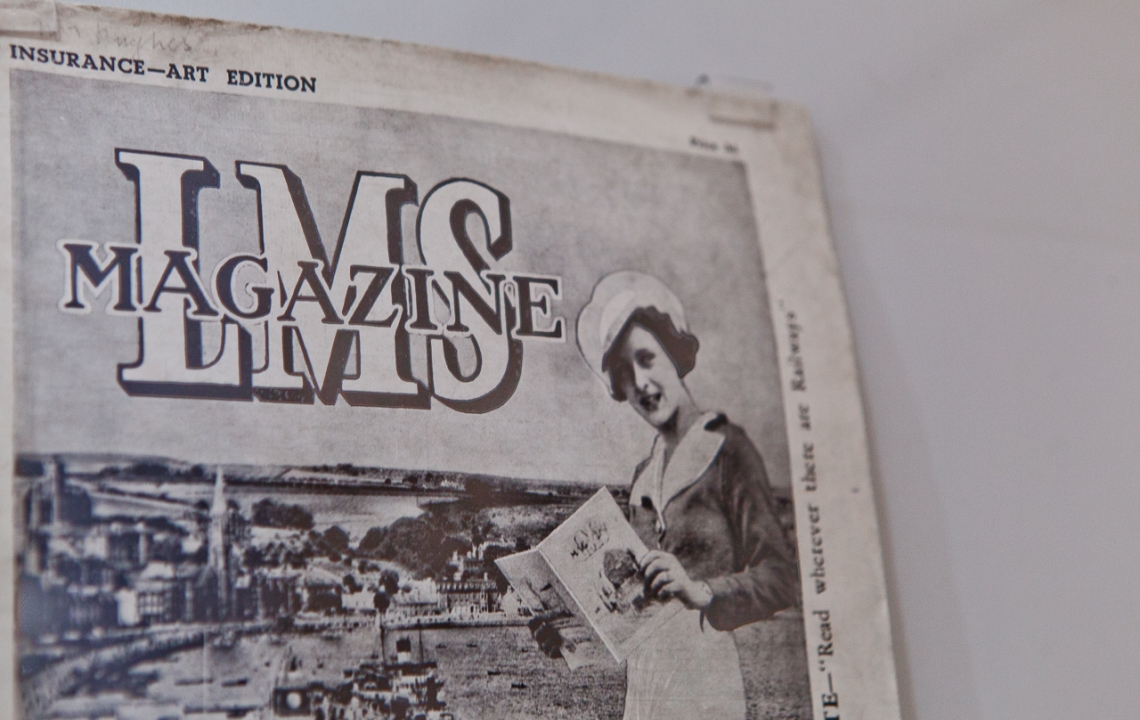

The walls feature printed publications from those years which mention the CGR, or information flyers giving news about the island’s railway. For instance, a front-page story on 21st January from The Lion (British Services Cyprus Weekly, 1972), describing the situation, at the time, with the road in the Dhekelia region.

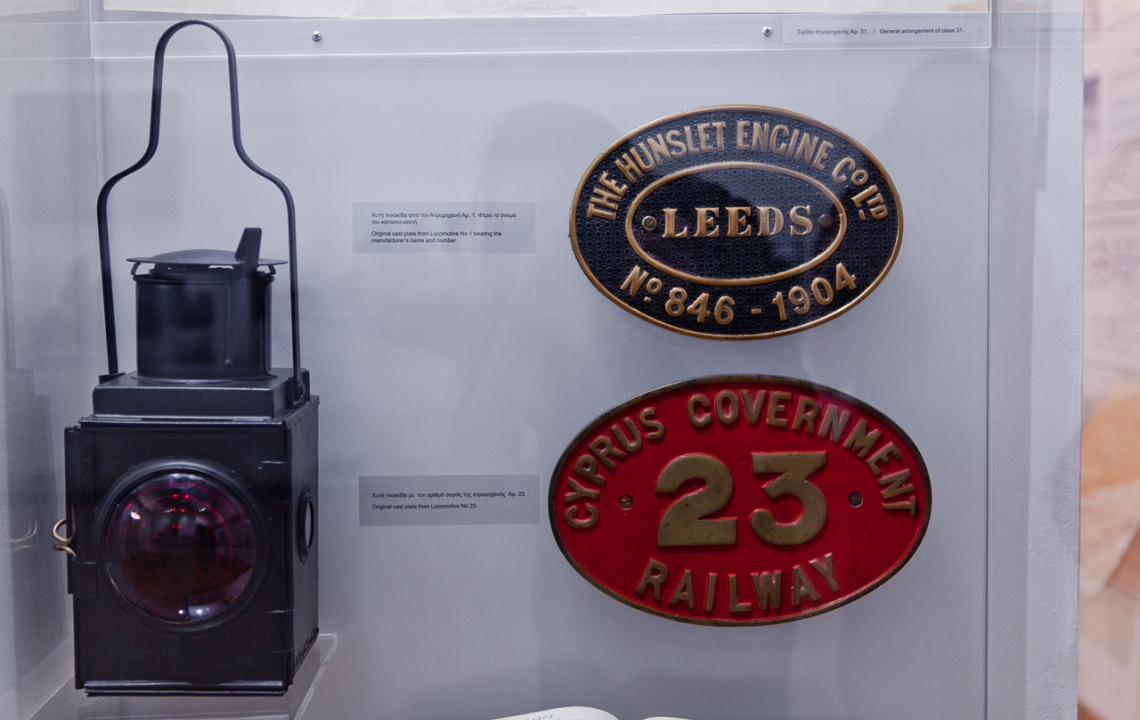

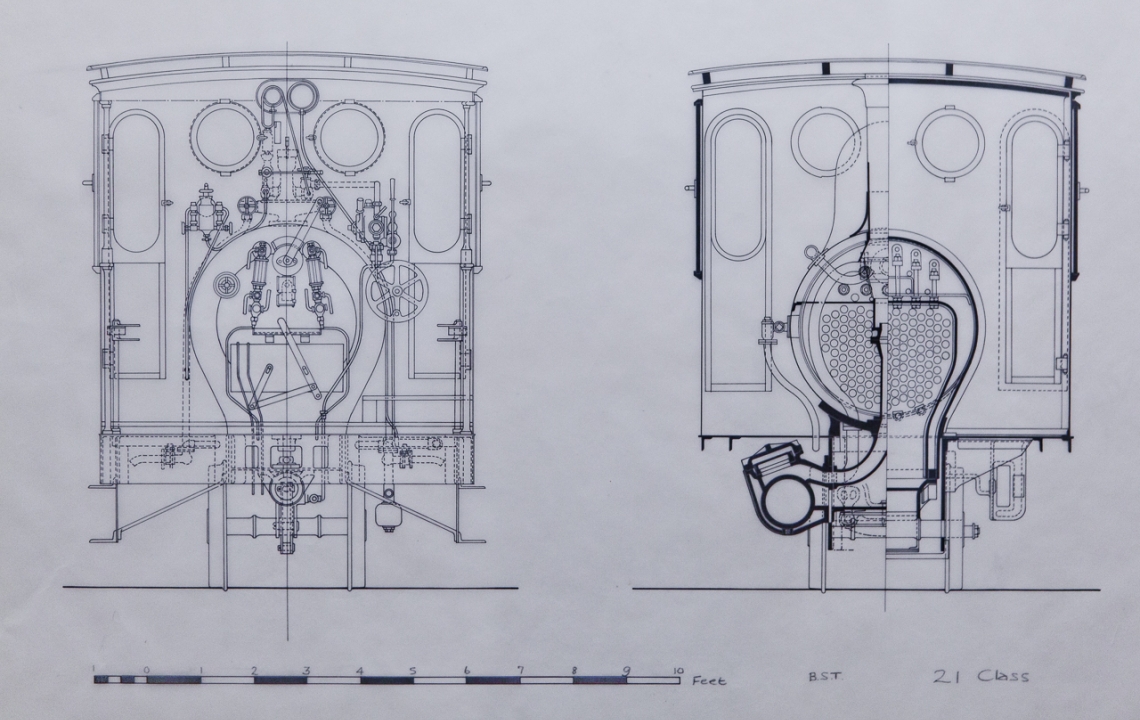

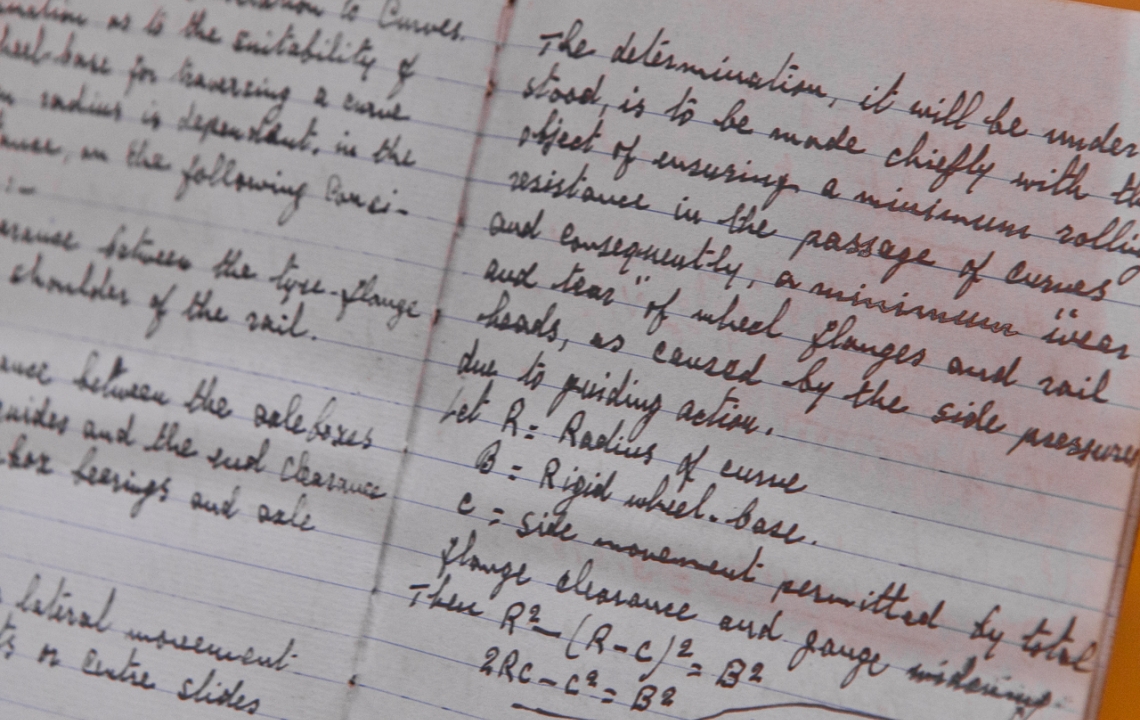

One of the vertical display cases features cast iron plates with the numbers “1” and “23” (they were attached to carriages and steam engines), in addition to a trackman’s light and a fascinating cross-section sketch of a steam-train engine. You also won’t have any trouble noticing that all these items were manufactured in Leeds (Great Britain).

We headed up to the top floor, where a bicycle with a basket has been set, which vendors would use to deliver food and drinks to arriving trains: needless to say, for travellers, the journey ahead across the island “was not a short one”. You can examine the luggage they would use, such as vintage suitcases, travel bags and others.

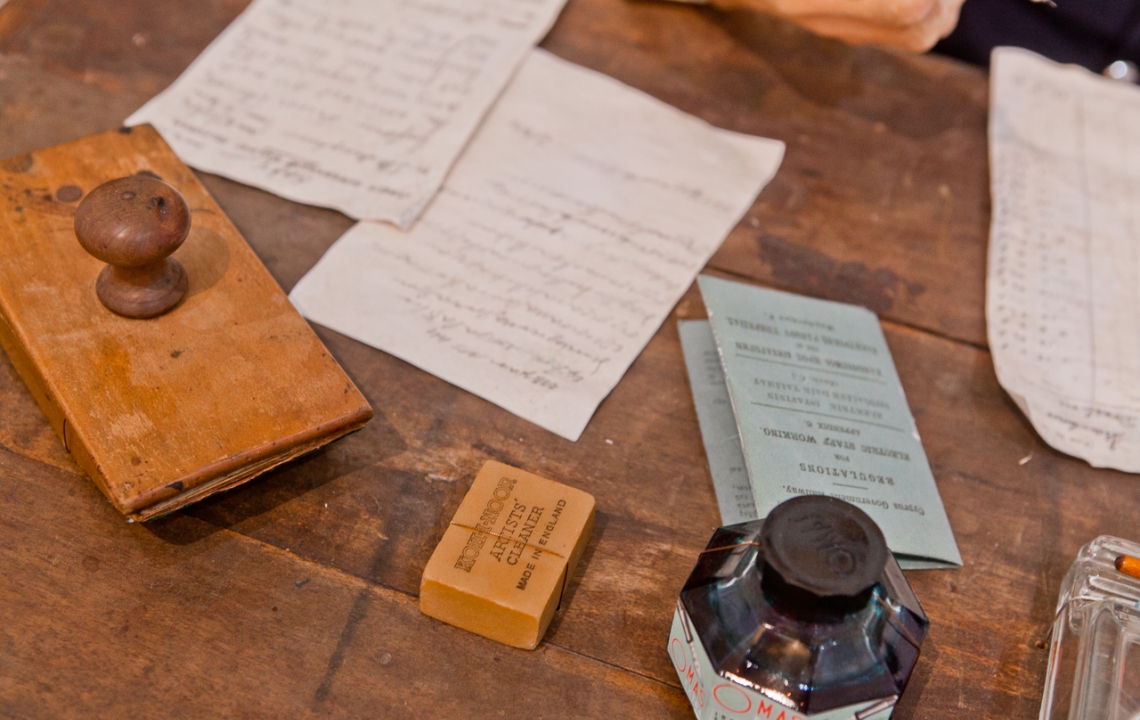

For those sensitive sorts: Try not to be startled by the mannequin of the station chief, whose piercing and very realistic gaze will meet you immediately as you walk into the halls on the second floor. I admit, every time I turned towards that figure, sitting with a tense posture, in a recreated office setting from past years, I shuddered.

The former station halls have been filled with stands featuring photographs and sketches, as well as a detailed image of the route from Evrychou to Famagusta, in an aid to improve the visual experience. The stands also display elaborate models of the station and locomotives (steam engines), as well as carriages with figurines of passengers inside. Besides this, there are mannequins dressed in uniforms and display cases with a collection of knick-knacks relating to this significant chapter in the history of Cyprus: tickets and timetables, fragments from carriage designs, lights, plaques from different years — this will be moving for everyone, both children and adults.

The exhibit observes a chronological system: not only are the images of the stations and the characteristics of the machinery shown for every decade, but a historical canvas is created and is this is by no accident; after all, the first half of the 20th century, as we all know, had an abundance of social upheavals and wars. A site as strategic as a railway station and the ability to communicate through it, albeit on the island, could not remain out of the action, but we shall discuss this a little later.

As you can observe, many of the exhibits on display were given to the Museum as gifts from private individuals, the majority of whom were Brits. The main benefactors were K.E Rook and T.H. Bagley.

The walls feature printed publications from those years which mention the CGR, or information flyers giving news about the island’s railway. For instance, a front-page story on 21st January from The Lion (British Services Cyprus Weekly, 1972), describing the situation, at the time, with the road in the Dhekelia region.

One of the vertical display cases features cast iron plates with the numbers “1” and “23” (they were attached to carriages and steam engines), in addition to a trackman’s light and a fascinating cross-section sketch of a steam-train engine. You also won’t have any trouble noticing that all these items were manufactured in Leeds (Great Britain).

We headed up to the top floor, where a bicycle with a basket has been set, which vendors would use to deliver food and drinks to arriving trains: needless to say, for travellers, the journey ahead across the island “was not a short one”. You can examine the luggage they would use, such as vintage suitcases, travel bags and others.

For those sensitive sorts: Try not to be startled by the mannequin of the station chief, whose piercing and very realistic gaze will meet you immediately as you walk into the halls on the second floor. I admit, every time I turned towards that figure, sitting with a tense posture, in a recreated office setting from past years, I shuddered.

One of the photos contains steam engines from those years, transporting carts through mines and pits on the island. A stand nearby also features a flyer from 1951, from the Greek newspaper, Ethnos.

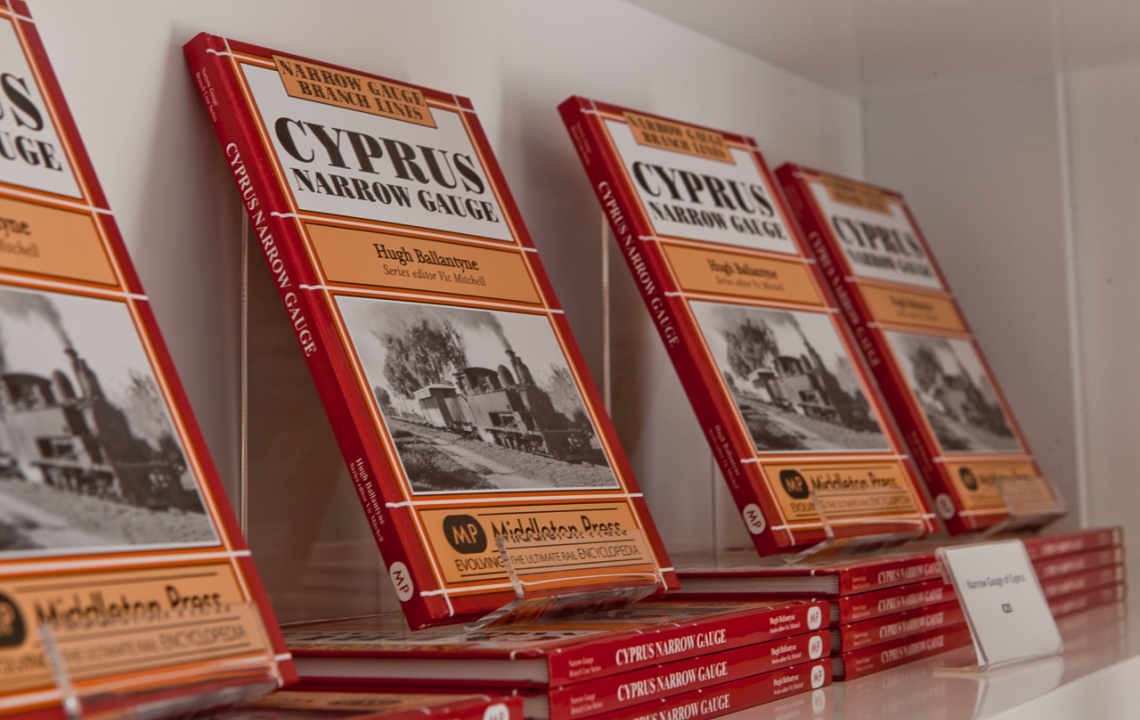

As you descend again to the first floor, don’t forget to take a look at the souvenir kiosk, where you can buy original souvenirs: posters, pens, pencils, porcelain cups imprinted with the Museum emblem and other things. Everything there is beautifully made, of good quality and well-priced.

After exiting the main building, we headed, naturally, towards the mail wagon nearby. It is open so you can climb up and look inside. True, not everyone will be capable of getting in there today — the narrow entrance parameters and the cramped size of the accompanying mail wagon will not let everyone “pass”, regardless of the hints it gives to the minimal level of comfort inside: small seating and letter cages, decorated in white along with the walls. Next is the carriage itself (small in size), locked and bolted, in which valuable loads and parcels were transported. It’s only after walking around its perimeter that you realise where the controller would be located — in essence, he was always on the outside of the carriage (his spot was offset behind the carriage wall and externally reinforced with metal; to put it bluntly, he would hang over the wheels).

But that wasn’t all: “on the tracks” in front of the carriage, there was an old (even ancient, based on its external appearance) draisine installed (I’ll explain this for the benefit of the youngest generation: a draisine was a trolley used to transport railway workers, which moved mechanically along the rails).

Opening Hours:

Winter (16th September – 15th April): Monday-Sunday 08:30-16:00;

Summer (16th April – 15th September): Monday-Sunday 9:30-17:00

Telephone: +357 22933010

Free Entry

In the Village

After visiting the Museum, it wouldn’t be a bad idea to go for a stroll around this idyllic village, to see the traditional architecture of its houses and have a chat with the calm, kind-hearted locals. It’s easy to notice that they keep Evrychou in shape; even the deserted buildings — for instance, the old bakery, which we unexpectedly came across — didn’t give off the impression of being neglected…

The quiet, picturesque alleyways swiftly run down from the hills, only to then soar abruptly, as you head around the corner to the next summit, entangled in all manner of greenery. You can see apple and apricot orchards, acacias and thickets of cactuses lying amongst traditional village houses, with geranium-filled flowerpots everywhere you look; their reddish-pink wisps glitter in the sunlight from all the ledges, steps and balconies.

The architecture consists of small, compact, two-storey houses, built from locally-quarried stone (lime), like ledges towering over the hillsides, with their obligatory balconies, verandas (most often wooden) and sloping tiled roofs. You can encounter bungalow doors, usually glass, which are concealed by finely crafted metal cages, decorated with images of birds and flowers.

The centre of Evrychou is a small square with an old basilica attached to the bell tower of Agia Marina (1872) and a cosy, modern cafe situated nearby. There is a fresco of Saint Marina located on the right of the entrance into the church. It’s worth taking a walk around the church premises to feast your eyes on its architecture.

In general, there are several churches located in the village: a medieval church, dedicated to Saint Kiriakos, as well as the old Church of Saint Georgi and the more contemporary build of Saint Cara.

A little piece of history: A. Gaudry, the author of the book “Recherches Scientuque en Orient”, mentions that until the mid 19th century, the best cotton in Cyprus was manufactured in Evrychou. The village gained considerable significance under British rule, due to a series of infrastructure projects which were carried out over those years. One such example was the construction of the road to Nicosia, which was completed in 1899. Once a large village, Evrychou has had a police station since 1905. Although it became operational in 1905, the railway only connected Evrychou to the other stations in June 1915.

Several versions exist regarding the name of the village. The most popular suggests it gained the title due to being the only settlement in the region which enclosed a vast territory: “Evrys Chous”, Ancient Greek meaning “large area/land”. According to the second interpretation, legend has it that the village name was given by folk from other regions, who resettled there after finding an abundance of fertile lands (“Ev Chous”, or “good land”). Another version suggests that the village possibly received its name from the first settler here — Evrychios.

Whatever the case may be, the village is mentioned in old maps (1573) as “Eariko”, while Mas-Latri describes the settlement as “Eurichou”.

Evrychou is one in a small chain of beautiful villages in the Troodos foothills and the Solea Valley. Whether you’re on the way home from the mountains after going for a picnic in Platania, or you’ve been wandering around Old Kakopetria, favoured by both locals and travellers, you might be in the mood to try some trout in lemon sauce from one of the village restaurants — if so, turn off the busy main road at the sign for Evrychou and simply go for a stroll along the village streets, as they trustingly meet you with open arms.

Around every turn, fascinating views of the hills are revealed; darkened doors and gates which have survived from earlier times, old bakeries and barns with clay masoned walls… here you can see the whole, unhurried lifestyle of a Cypriot settlement, verified by many generations, away from all the hustle and bustle of our everyday lives.

Come for a visit, kick back and walk around to your heart’s content.

Useful Advice:

How to get here: If you’re driving, take the B9 from Nicosia; from Limassol — the B8: go from Polemidia to Troodos, then further on through Sattias to Kakopetria and Evrychou.

Parking: Available at the village entrance (by the local police station), or in the centre — opposite the church, where there’s also a bus stop.

Buses: 404, Archbishop Makariou stop.

For more information about the village and its Museum, please see here: www.evrychou.org.cy and www.mcw.gov.cy

Have a great time and see you soon!