There is one museum on Cypriot soil which you need to be ready for when visiting. Regardless of how well you might know the local history and the many dramas the Cypriot people have repeatedly had to face over the centuries. To put it bluntly, this exhibit is not only capable of shaking you up, but shaking you out of your habitual, calm perception of the world, of sharpening your feelings and most likely, making you be grateful to fate for not having gone through something similar.

Today I’m going to tell you about my visit and you can decide for yourself whether you want to know “everything” about Cyprus, or whether you’ll limit yourself to those unequivocally positive “tourist” and “beach-filled” experiences.

-

The museum was founded two years after the end of the freedom struggle in Cyprus, led by the organisation known as EOKA (1955-1959). The decision to end the conflict was made on the 26th January 1961 and published a month later in the Official Gazette of the Greek Communal assembly.

The main aim of the museum’s creation was to preserve the people’s memory of events relating to the Cypriots’ struggle for freedom. Organisers were tasked with forming archives, collecting historical material and popularising any information linked to this topic.

As a historical and scientific centre, the Museum interprets the concept of the National struggle by shedding light on the activity and fates of the EOKA fighters, using a series of visual effects: photo and video materials, as well as displaying unique materials in the exhibit. All of this is designed to encourage visitors, as is stated on the municipality of Nicosia website, “to search for a deeper meaning” in the events of the country’s relatively recent past and to get a sense of the “Fighting spirit”.

Nowadays, the Museum operates in a new building which opened on the 30th April 2001. Ten years later, it had already welcomed 27,000 visitors, the majority of whom were students and foreign tourists.

-

The modern exhibition is positioned over several levels connected by a ramp (very convenient for all visitors). You can pass through and get acquainted with the exhibits in both directions: either starting with the lower floor and working your way upwards (for those who have little or no knowledge of this dramatic, heroic and simultaneously multi-episodic chapter in the history of Cyprus, there is introductory information available downstairs), or from the top to bottom floor.

I chose the second option in order to immediately gauge the exhibit’s concept and form the most well-rounded impression. So I invite you, if you still decide (dare), to follow me…

Let’s begin with the main part and discuss the events which took place on the island from the mid to late 1950s, resulting in Cyprus acquiring its long-awaited independence in 1960.

EOKA and the National-Freedom Movement: 1955-1959

In Greek: EOKA is derived from the abbreviated form of the Greek Εθνική Οργάνωσις Κυπρίων Αγωνιστών (The National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters). This was the name given to the guerrilla organisation of Greek-Cypriots who set themselves the following political aims: “liberation from British oppression” and achieving self-determination on the island.

EOKA is said to have been formed on the 1st April 1955 (this date was alleged to have been chosen in case there was an information leak, as the political opposition wouldn’t believe it, considering it to be an April fool’s joke!).

In the initial Declaration of its founding, EOKA (led by Georgios Grivas [1], a truly controversial individual) neglected to set “Enosis” as one of its aims to achieve (furthermore, in 1957, Archbishop Makarios refuted it, striving to preserve Cypriot sovereignty).

Nevertheless, Enosis — the notion of а historic union between Greek-Cypriots and native Greeks — began to resound from time to time, beginning in the early 19th century. It manifested again in the first third of the 20th century and didn’t go amiss by the British. The United Kingdom promised the Greeks reunification, providing that Greece fight in the First World War on the side of the allies. As we know, the offer was declined due to the family ties of King Constantine I with Kaiser Germany.

However, the hopes and ideas of a historic unity have been, as they say, distinctly up in the air for subsequent decades…

Meanwhile, the leadership of the AKEL (Progressive Party of the Working People of Cyprus) opposed military action, advocating acts of civil disobedience (strikes, protests and demonstrations). In addition, based on the results of the 1950 AKEL plebiscite (which, for obvious reasons, was boycotted by Cypriot-Turks), it became clear that the overwhelming majority of Greek-Cypriots were in favour of unity with Greece (98%).

Ultimately, the intentions of the independence fighters characterised EOKA as a political, rather than a military organisation. In the words of Grivas, it wanted to draw worldwide attention to the issue in Cyprus by conducting “high-profile operations” which would land in the headlines of newspapers.

By and large, the selection of group members was orientated around the “idealistic” and “passionate” youth, who weren’t burdened by families and economic relations with colonial authorities [2].

And so the founding of EOKA was simultaneously marked by the emergence of another campaign, the main aim of which was the British military on the island — close to 30,000 people [3]. Directly in line behind them, as enemies of independent Cyprus, were pro-British organisations and establishments, Cypriot informants and traitors loyal to the “occupants”, as well as the Turkish extremist group TMT (translated from the Turkish: Turkish Resistance Organisation), which had emerged in 1957.

It’s worth noting that against the background of the liberation movement, the strong push to develop international and inter-communal discord in Cyprus, which had been aggravated as a result of the anti-Greek pogrom in Istanbul [4], served the actions of the English. As such, one of the first orders of Field Marshall John Harding, who in 1955 had been newly appointed to the post of Governor of Cyprus, was to expand the numbers of auxiliary units in the Cypriot police force. This was achieved at the expense of recruiting a disproportionate number of officers from the Turkish-Cypriot community. Moreover, while ignoring the interests of the Greek populace, the new Governor ordered the creation of a subdivision — a “special mobile reserve” — which would enlist solely Turks.

At the peak of the fighting, EOKA’s paramilitary formations numbered 1250 participants (250 of whom were permanent members, while the other 1,000 were active members of the underground movement). As is stated in a number of sources, the Greek government supported EOKA in secret, by supplying them with arms, financial backing and spreading propaganda through radio broadcasting stations in Athens… We’ll return to this issue when we discuss the history of the schooner “Agios Georgios” at the end of our tour.

In total, 1144 armed clashes with the British army took place on the island: more than half of them occurred in urban regions, with the remainder in rural localities.

Losses were incurred on both sides: EOKA and the peaceful Cypriot population lost 148 people, 69 were wounded; 105 British servicemen were killed, as well as 51 police officers.

EOKA activity continued until a ceasefire was announced in December 1959, which led to the London and Zurich agreements signed on the 11th February by both Cypriot communities, in addition to Greece, Great Britain and Turkey. Its regulations lay at the basis of the constitution of the independent Republic of Cyprus, thus seriously limiting the country’s sovereignty. They further led to an aggravation of inter-communal relations on the island and caused a series of internal crises, the consequences of which can still be felt today.

In general, numerous publications, for instance, this one in the Cyprus mail and others, are today dedicated to discussing the EOKA theme.

Inside the Museum

You’re immediately exposed to a large, emotional surge of information, but that’s understandable. I’d even say: if you’ve come here while taking a quiet, absorbing stroll around the Old town, then you’ll have to, ah well, it won’t be easy for you to take this in. The National Struggle Museum plays on all your senses. Almost without warning, it wedges a sharp blade into all the “holiday” moments you’ve experienced beforehand.

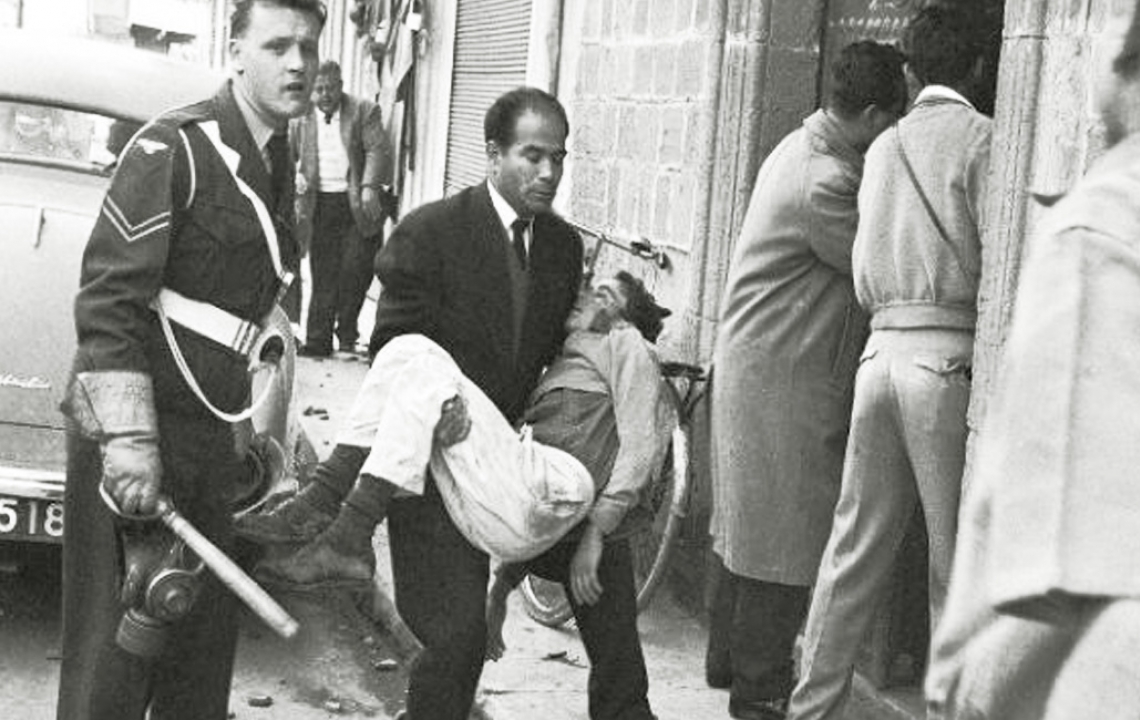

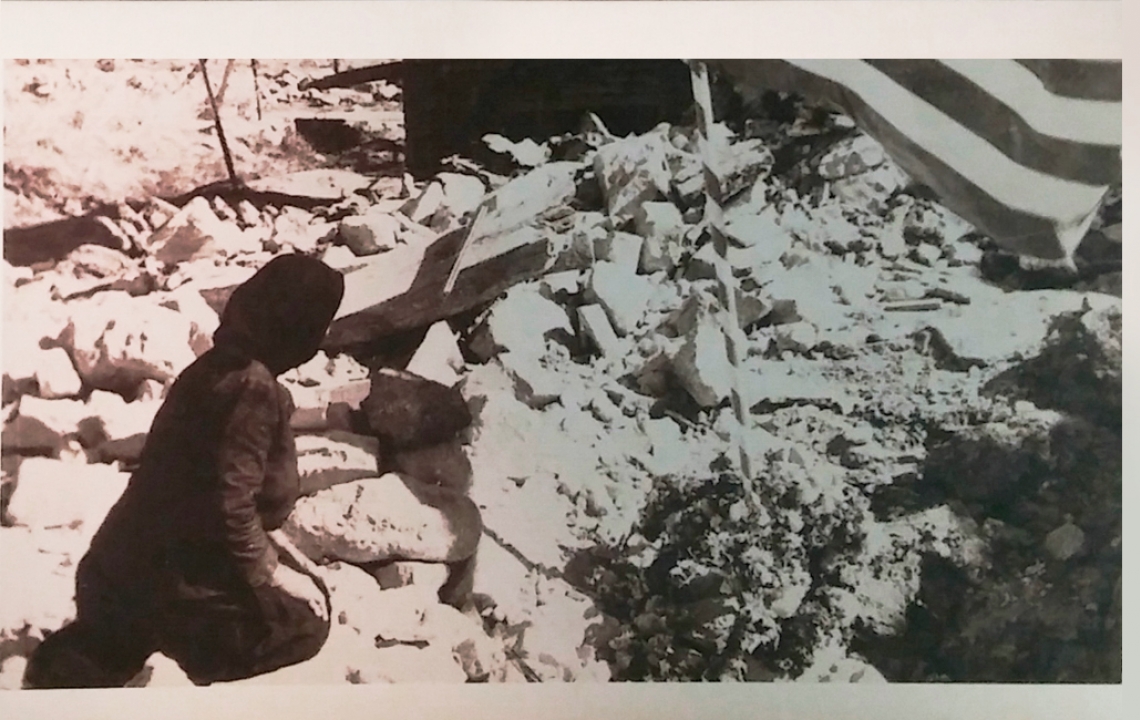

Its exhibits will continually make you feel how your heart clenches as you see the documental chronicle of the sufferings which the people of Cyprus endured as a whole. Even more so when you’re surrounded by chilling photos of tormented victims, the places of their untimely deaths or real-life “artefacts” (I apologise immediately!) used to execute those who fought for the liberation of their land — both the old and the young, who didn’t even get the chance to live life to the full.

A memorial to the fallen has been constructed on the upper level. Candles “burn” in each niche with a portrait and a short account of each victim: their name, when and where they were born, in addition to whether they died under torture, in the course of the fighting or were executed by members of the movement… So many faces and human lives [5], which someone once ruthlessly instructed in order to accommodate their political gains, not wishing to lose their influence in the region.

The greatest level of tension is created by three rope loops hanging on a beam above the exhibit, similar to those which the British used to dispose of EOKA members. Be prepared, nevertheless, to see an “exhibit” which is rather difficult to come to terms with — a genuine noose, one of three which executioners used on Cypriots (the other two, as the information states, lie in the British “collection” and in Nicosia Jail, where they once performed executions and later committed the dead to the earth [6]. Such was the price of freedom for the people of Cyprus in those years!

In addition, what is perceived as especially blasphemous was how authorities at that time even had photographs taken of themselves, for the archives, on the day when the doomed were to be executed.

The authorities at that time even had photos taken of themselves for archiving — on the day when the doomed were to be executed — a move which was perceived as especially sacrilegious.

These photos — the final moments in the lives of the condemned heroes, where there’s a strong feeling that these hard-spirited individuals realise what is about to happen and are bidding farewell to their lives — are positioned in one of the display cases around the very noose which took their lives.

You will be surrounded on every level with stands featuring enlarged photographs, in which the events of those years have been permanently documented. Believe me, even today, it still isn’t easy to be around old photos which incite a cascade of rage, grief and suffering!

It begins with archived materials, letters from EOKA fighters to their loved ones, their manuscripts and so on. For those studying this period of the island’s history, the exhibits in question will help you reveal the historical truth to its utmost. From here, as from newspaper publications, for instance, (not only Cypriot, such as Phileleftheros, but several foreign papers), it becomes clear that EOKA gained fame and support from abroad. For instance, in December 1955, an article was published in the French daily L’Express in support of EOKA, by the Franco-Algerian writer, Albert Camus.

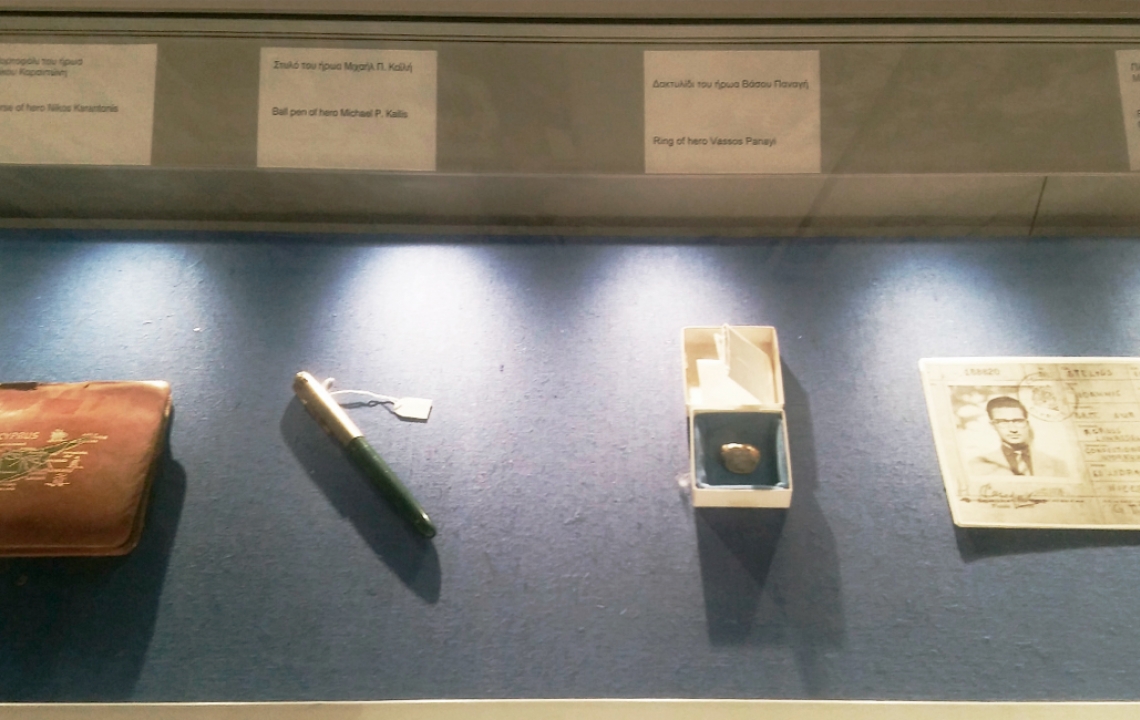

Naturally, you can find a lot of information dedicated to the most prominent figures in the movement. One example is Michalis Karaolis [7] (1933-1956), a native to Palaichori — not only will we find his letters and diaries in the collection, but personal belongings, together with items of clothing (or, more accurately, their remains) which have been carefully preserved.

A memorial to Ioanna Zachariadou [8], one of the youngest victims of those events, has been assigned a separate space in a large display case, featuring her embroidery work and a studio photograph. She died in Famagousta on the 3rd October 1958.

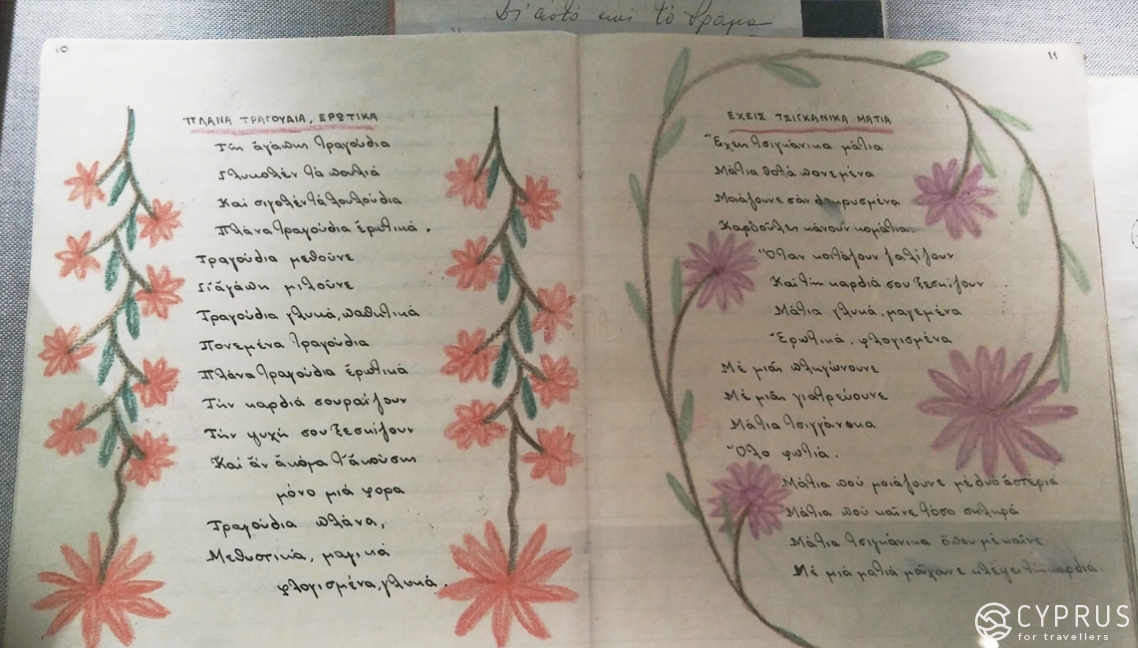

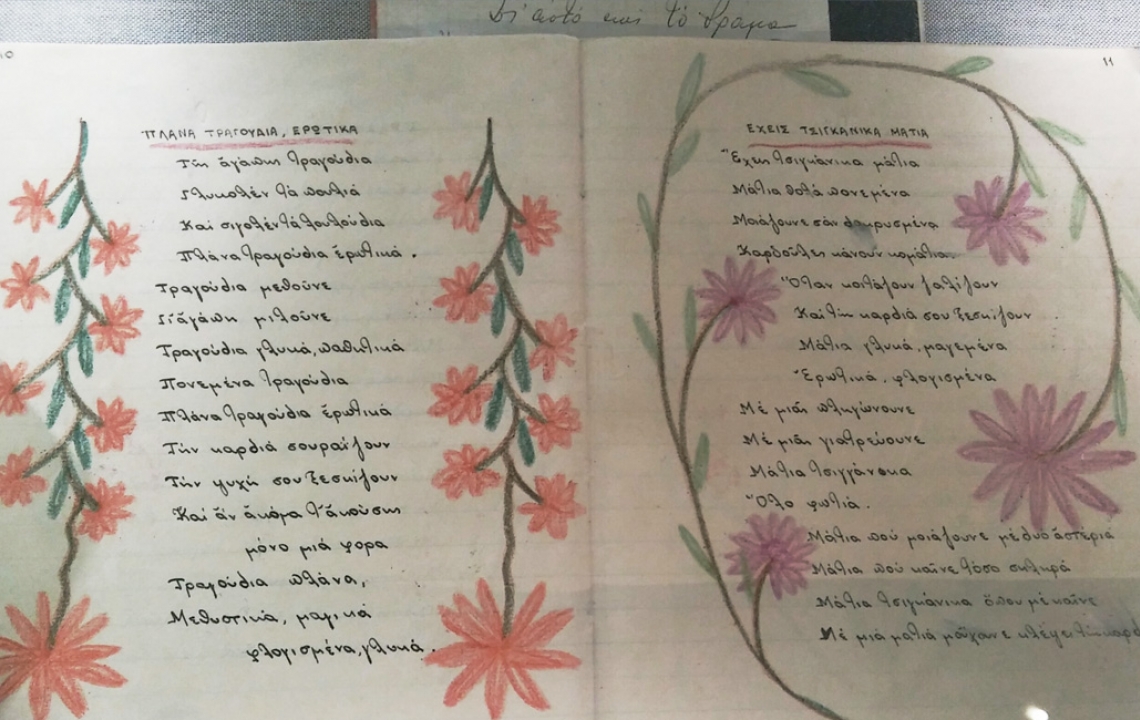

On the second shelf of these horizontal display cases, we can see books and exercise books (likely from school), as well as items belonging to EOKA heroes — some of whom had just finished school or were simply very young. Part of the items belonged to Stelios Mavrommatis [9] (1932-1956) and at the centrefold of a hand-made book, diligently decorated with floral images, you can see words to the Greek folk song “You have Gypsy Eyes…??” (Έχεις τσιγγάνικα μάτια). They’ve been written in calligraphy with an ink pen.

Nearby, you can see a large photo depicting the moment Cypriot women rallied to protect their husbands and sons, attempting, at least, to somehow ease their fate.

Immediately after, like a voiceless testament to the futility of their efforts, you can see scenes from the execution of the “rebels”: aside from hangings, the authorities “actively practiced” shootings — while staying their ground — right there on the streets… The display cases also feature several bullets extracted from the bodies of executed victims, with their names stated.

As is the case in several parts of the exhibit, enlarged images are featured of the fighting in the village of Kourdali (1958) and other localities, where, aside from the fighting, the unfortunate victims of gunfire are depicted: children, women, and old men…

As I said: this exhibition isn’t for the weak of heart!

Another memorial “wall” has been set up opposite these photos which, amongst others, take a heavy toll in comprehending. The wall lists the names of all the EOKA heroes, indicating the age at which they died.

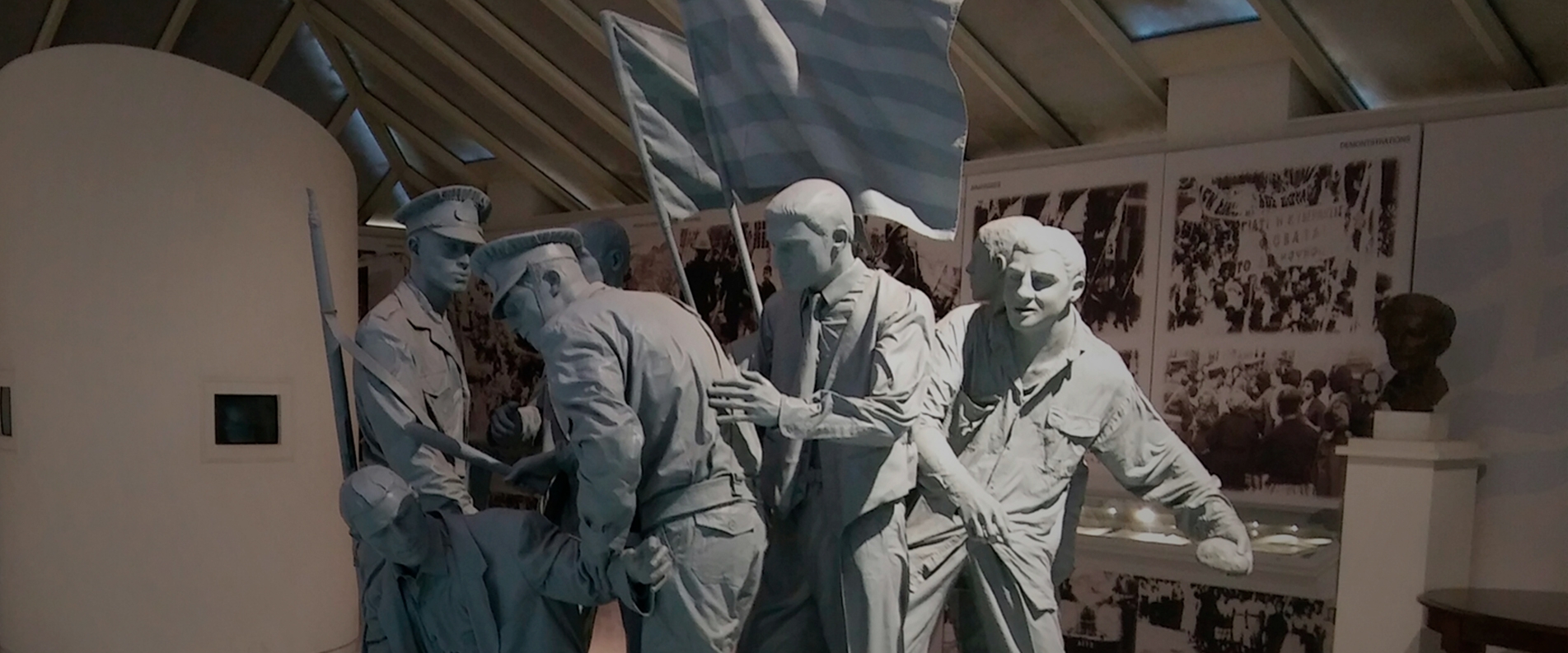

As is known, many of the movement’s members became inmates in English prisons and camps: in the centre of the hall, you can see a reconstructed prison cell with a detainee sitting behind bars. In the same hall opposite, there is another sculptural composition, dedicated to the guerrilla fighting of the EOKA members.

Separate parts of the exhibition have also been assigned to individual people. For example, we can find yet another chilling photo, this time picturing Kyriakos Matsis [10] (1926-1958), who perished in the village of Dikomou (November 1958). His personal belongings (jade rosary beads, a torch, binoculars etc.) lie next to the image.

In one of the subsequent display cases, you can also see a multitude of exhibits along the whole wall, donated by the relatives of deceased fighters: these are mainly personal, everyday items, books, favourite musical instruments (bouzouki, mandolin), as well as the hockey and military uniforms of Michalis Karaolis, Ellias Papakyriakou and others.

Aside from photographic evidence, a reconstructed guerrilla shelter is featured in the section of the exhibit on guerrilla activity and the death of Grigoris Afxentiou (his underground nickname was Zidros/Ζηδρος) near Machairas monastery [11]. There is also a “wanted” poster and even a handful of the earth collected from the spot where he was burned to death [12].

While going lower and lower, we come face to face with archived documents and memorable items relating to an earlier period: after all, as you recall, we are doing this “backwards” — as though we are unravelling the events of those years, from the results of the struggle to the first manifestations of the national liberation movement.

So, while gradually descending and studying (as much as we can, of course) the displayed exhibits and archives, we found ourselves on the lowest floor.

Thanks to the large display cases, featuring samples of EOKA armaments and ammunition (discovered and confiscated in those years by British authorities), those who love weapons history will have something to learn about.

Nearby you will find photos of places where guerrillas hid from their pursuers, as well as items used in secret shelters and “head-quarters”: radio receivers, items of clothing, footwear, books… You’ll, therefore, see the earliest photographs illustrating the very beginning of the organisation which fought for Cypriot independence.

In addition, visitors can view flyers (printed on a typewriter) in display cases, which were distributed by members of the EOKA movement and other pro-independence organisations and parties. The display case also features the Evangelion, together with the Oath Protocol (Πρωτοκολλο Ορκωμοσιας, Athens, March 1953) — it was written on standard lined paper (the first signature, in red ink, as is customary for the Archbishop, belongs to Makarios III, after him — all those who were present in that historic moment (11 in total). In the same hall, you can even see the desk at which the document was signed.

Several busts and photographs of General Grivas Digenis, Archbishop Makarios III (1913-1977) [13] and their personal belongings (geographical maps, books, clothing and others) are also present in the halls.

An interesting fact: the photos tell the gripping story of a well-known failure which EOKA endured at the early stage of its activity: this concerns the schooner “Agios Georgios”.

If you recall, I mentioned at the start of this piece that Greece was likely involved in supporting the Cypriot liberation movement. Well, the time has come to tell you about a famous episode in the movement’s history.

So, on the 25th of January 1955, the ship, along with its seven-man crew, was captured on a shelf by the village of Chloraka (near to Paphos) by the Royal British fleet. The ship’s mission had been to secretly transport ammunition from Greece, which was to be used in the future fight of EOKA.

-

Getting back to the exhibits — situated nearby the pieces dating back to the first half of the 1950s, there are those which tell you the story of before EOKA’s emergence: display cases dedicated to the events of 1931, the so-called “October revolt” (21st-23rd October), when after two days and thousands of demonstrations, the rebels demanded the British immediately remove themselves from their country and set fire to the Governor’s residence in Nicosia.

Further on, in another assigned section, you can see display cases with artefacts dedicated to the island’s long and glorious past. They are a testament to how Greece and Cyprus have developed “hand in hand” for centuries [14] and this, as we know, has served to further develop the concept of Enosis. There are antique coins from the era of Pnitagoras, the king of the city-state of Salamis (351-332 B.C.), an iron sword (from the royal tomb in Salamis, 7 B.C.), a stone relief and others… The book on display here is an old folio «Προς Μητερα Ελλαδα» noting the results of the Referendum of the Greek communities, which took place on the 25th March 1921 and was timed to coincide with a century of the Greek revolution.

-

And so, our look around the exhibition has turned out comparatively well. Now, all we have left is to “digest” the salvo of rather complex, profound feelings which have bombarded us and given us food for thought…

One addition: The Museum also provides visitors with the same video for viewing. You won’t have any trouble finding the displays, both in the exhibition and in one of the rooms on the lower floor, next to the lecture hall (by the way, photo materials are also featured here: they are dedicated to the stage when EOKA members, now in confinement, had been gathered by the British in prisons and camps and judging by the expressions on their faces, didn’t have the slightest idea of their fates ahead).

Address: Archbishop Kyprianou Square, Nicosia

Telephone: +357 22305878

Email: info@meae.org.cy

Opening Hours: Monday to Friday, 8:00-14:30

Until Next Time!

[1] G. Grivas (1897-1974) was a Cypriot and general of the Greek army, he took part in both World wars. During the Nazi occupation of Greece (in the course of WWII) he led a far-right resistance group, which he was part of during the Greek Civil war. Grivas didn’t take the pseudonym “Digenis” (under which he secretly returned to Cyprus in 1954) at random, — this was a direct reference to Digenis Akritas, a legendary warrior from the Byzantine empire, who protected its borders from invading aggressors.

[2] The middle class of those years flourished thanks to involvement in international trade, which was supported by British authorities.

[3] Note: Be that as it may, deserters from the British army often crossed to the side of the Cypriots.

[4] An anti-Greek pogrom (Istanbul, 6-7th September 1955), which became one of the most significant of many others (as you’re aware, the revolt on the Christian people who resided in the territory of the Ottoman Empire, was a part of the internal politics in the 19th-20th century). People died, Orthodox places of worship were destroyed and the city’s infrastructure was damaged. The chaos spread its way to Ismir, however, the NATO troops located there, along with the Western-European public, preferred not to interfere.

[5] It’s well known that Cypriot chronicles have carefully preserved not only the names of heroes, both men and boys, but also female Cypriots, who fought for freedom. As I was informed by a Museum employee, a special section of the exhibition will be set aside for them in the future, where you will be able to find information on specific individuals.

In one of the resources: www.cyprus-forum.com username miltiades, a former witness to the events of those years, made a publication on the 26th August 2009, where he particularly stated:

“On the 26th June 1956 British troops ...killed OLGA KONSTANTINIDOU, more about her later.

Two women were killed by the British during the struggle, excluding the little girl. The struggle was very much dominated by the men, as women were not considered the “right material” for active action.

There were 12 main EOKA action units — TOMEARHIES, a further 10 secondary action units and a third unit known as Gamma ARHIGI SINDESMON of EOKA, consisting of 6 EOKA active members one of them being LOULA KOKKINOU...

Of the 12 A units one woman, ELENI SERAFIM was in the Larnaca unit from 6/9/1956 until [she was] arrested on 11/12/1956. On her release from prison she rejoined the Larnaca unit on 17/5/1958 until the end of the struggle.

Please note that our young boys and girls participated in the struggle by demonstrations, taking the OATH and carrying out “delivery” missions on behalf of the active units.

On April 26th 1956, 53 years ago today, a day I remember very well, a number of bombs were thrown at a British army truck, at the same time another attack took place in Famagusta.

It is notable that NO SUICIDE missions were carried out or ever considered as an option”.

[6] Colonial powers were very afraid of the national disturbances and rallies, therefore they decided to execute EOKA fighters and commit them to the ground specifically in this spot: Imprisoned Graves.

[7] Michalis Karaolis (1933-1956) became the first EOKA member to be executed by British colonial authorities. In 1954, he went into the service of the British Tax authority of Nicosia. A year later, as an EOKA fighter, Karaolis blew up his office: however, not wishing his colleagues to die, he set a timer on the bomb for a Sunday. A month later, together with two other EOKA members (Andreas Panayiotou and Yiannis Ioannou), he executed Herodotus Poullis, the constable of the island’s Greek specials division to the British police force, on Ledra street in Nicosia. From that moment, the authorities declared Michalis Karaolis a wanted man. He was soon after arrested by a Turkish-Cypriot police officer and turned over to the British. As a result, after his trial, he was sentenced to be hanged, which was carried out on the 10th of May 1956. His death resonated not only in Cyprus but also in Greece, where a wave of anti-British indignation had erupted, culminating in demonstrations and chaos.

[8] The girl was only 10 when she died from the horror endured as British soldiers burst into her home.

[9] Stelios Mavrommatis was an EOKA fighter, born on the 15th November 1932 in a village near to Kyrenia, the son of Christoforos and Eleni Mavrommati. When the war began on the 1st April 1955, Mavrommatis joined and took part in several sabotage attacks directed against British military planes. He also played an important role in gathering weapons for fighters, passed to them through private individuals. Amongst his comrades, there was his cousin, Evagoras Pallikaridis (1938-1957), as well as his brother and their parents. Mavrommatis was detained for his involvement in an unsuccessful attack on two British pilots in the Nicosia region of Agios Dometios. He was condemned and sentenced to death by hanging on the 21st September 1956, together with fellow EOKA members Andreas Panagidis and Michalis Koutsoftas, who had been arrested in the course of a different incident. After the sentence was carried out, all three were buried on the territory of the Central Jail of Nicosia.

[10] Kyriakos Matsis (born in Palechori) was also a guerrilla fighter and one of the first EOKA members. On the 19th November 1958, he was discovered, as a result of betrayal and surrounded together with two other guerrilla fighters in the house of Kyriakos Diakos. He was killed by the attackers in the course of the shoot out which arose.

[11] Nowadays a memorial to the Cypriot “Eagle” (the Cypriot people gave Grigoris this nickname) is located here. The Museum was opened under the monastery’s walls, while on a viewing platform, soaring above the valley in the Troodos foothills, a monument towers to this hero. A hero from whose legs burst the powerful wings of an eagle — a bird, which, like Grigoris, is always ready to sacrifice its own life in the name of freedom.

[12] I’ll remind you of the main facts from the life of one of the most well-known heroes amongst Greek-Cypriots. A native to the village of Lysi, Afxentiou in his early life had strong hopes of becoming a footballer, then he served in the Greek army and later became second in the EOKA hierarchy, after G. Grivas. He then orchestrated attacks on two buildings: CBC — a pro-British television station and an energy company in Nicosia. It was Afxentiou who thought to use the missile shells from British ships which had been discovered in the shallows as explosives, — consequently, the British declared him a wanted man (5,000 pounds sterling was promised for his head).

Having sought shelter in the Pentadaktylos range, Afxentiou began to educate his fighters on the skills of guerrilla warfare. Later, in October 1955, he and his comrades-in-arms raided a police station in Lefkoniko and seized the entire British armoury there. By order of Grivas, he relocated to the Troodos mountains, where on the 3rd March 1957, after he had been betrayed by a local shepherd (who was consequently transported to England and hidden) The hideout of Afxentiou and his comrades was uncovered: having ordered his friends to surrender, Grigoris fought until the end… and after losing their patience, the enemy doused the entrance in petrol and set fire to it. The charred remains of the hero, as well as many others from those years, were buried on the territory of the Central Jail of Nicosia.

[13] Including the period of his “Seychelles exile” (having refused to accept measures enforced by the English during negotiations on the 5th March 1956, which aimed to regulate the situation in Cyprus, Makarios was arrested and exiled to Seychelles. The display features his suitcase, elements of his attire and thurible, as well as black sandals.

[14] As is known, the “Greece-ification” of Cyprus happened long ago, thanks to the arrival of the Mycenaeans to Cyprus in 14 B.C., who were soon after “followed” by the Achaeans.