All three villages that we want to tell you about in this series are located in the Lefkara region («lefka ori» means «white hills» in Greek) and used to be called «Lefkara» thanks to its white building stone and various arts and crafts.

We begin our «trilogy» with a trip to Kato Drys.

It is a small village located to the south-east of Larnaca, next to Pano Lefkara (4 km) and Vavla (6 km). It is situated 520 meters above sea level in hilly terrain with narrow, deep valleys through which flows the Agios Minas river.

Kato Drys is currently home to 130 people. The name comes from Greek and means «bottom oaks».

The main street, which is also the liveliest street in the village, is home to a traditional Cypriot kafenio. There is an old-fashioned British sign that hangs under its awning that pictures a fox holding a quail in its mouth (we will learn the story behind it later).

Across from the kafenio is a map of Kato Drys. The walls of the surrounding houses are decorated with stenciled patterns — part of an international youth project.

If you walk around the village, you will discover two museums dedicated to rural lifestyle: one is a typical village mansion and the other is the Museum of Bee & Embroidery.

Meanwhile, we keep moving (albeit with some hesitation since many of the streets are missing names and the signs are sparse) towards one of the local agricultural museums (former residence of Papachristoforou).

It is easy to notice that many of the houses are uninhabited and are either in good or bad shape. The area is known for its almonds, which is why there is an abundance of almond shrubs in the village itself as well as its surrounding territory.

A tip: try to fight the obvious temptation to take a peek inside the empty courtyards and snap a photograph. The old brickwork can easily begin to break down. Just like in the neighboring Lefkara, most of the streets are covered in stone. Bigger streets feature examples of «Italian» architecture and houses with tile roofs. We are once again amazed by the type of white stone used to build all of the houses in the Lefkara region. It is the same stone that is used to cover most of the streets. This method — of using whatever material you had on hand — was commonplace in Cyprus. And yet in other regions the stone used in construction is usually softer and more porous (oftentimes it is limestone or sandstone), which hardly ensures the longevity of the buildings.

Agricultural Museum: a door in the wall

As you enter a scenic and narrow side street, tangled in geranium and jasmine thicket, you suddenly come across a gate leading into a courtyard, which is actually the beginning of an exhibition.

We were surprised when we learned that after you purchase your ticket, you will receive a set of keys to the house. So please behave responsibly and treat the museum with respect when you explore it on your own.

After we opened the first door on the first floor we ended up in a home bakery (which also happens to be the staff room). You can tell that the the house has been almost perfectly preserved. All of the household objects and appliances are openly displayed and include a couch covered with handmade mats, wooden bread molds and wash tubs. There is a small storage closet that contains baskets and pitchers and connects to the living room (there is also a separate entrance from the courtyard), which is the largest and most festive room in the house (the walls have been painted blue). This room features elements of rural luxury, such as an antique mirror with an elaborate baroque frame (gold-plated), carved furniture, a weaver’s loom and a carved chest with pieces of hand-spun textiles. There is a decorative panel on the wall made with silkworm cocoons: a floral pattern forms the frame to an old photograph of a couple.

Exiting into the courtyard again we look around and see a still, which was once used to make homemade zivania (it’s become clear by now that almost every Cypriot villager had one in his home), a pile of firewood used to heat up the still and a millstone used to make grape juice. A zivania still such as this one could yield up to 10 liters of liquid at a time.

We take the outside staircase to get to the second floor, open an antique door with the key that we received when we purchased the ticket and enter the main quarters. There is a large bedroom with the owner’s canopied bed in the middle and a bassinet next to it. Both the bed and the bassinet were made of metal by a British company and were mostly likely a sign of high social status. The floor is covered in rugs.

Pay attention to detail: it is easier to understand rural lifestyle if you pay more attention to the details and nuances. They let you better understand and appreciate a time period that is now long gone. So, for example, there is a pair of hobnailed, leather boots next to the bed and a portable furnace nearby. These objects give a glimpse of life in the winter, when it would get so cold that one needed a pair of hobnailed boots to get around icy roads. And judging from the relatively small size of the boots, one can assume that their owner was also quite short.

There is a set of decorative plates hanging on the wall across from the bed: English porcelain together with traditional Cypriot ceramics.

There is also a sample of locally produced embroidered silk displayed under a glass cover. Although it may look soft, the fabric was actually quite rough — similar to shantung or organza. There is a display case with a vest and the ubiquitous Singer sewing machine — a true symbol of the time period (these sewing machines were introduced at the end of the 19th century).

As we exited and locked the door behind us, we said goodbye to the museum attendant and passed by the list of museum benefactors.

Working hours:

Everyday except Saturday 9-3pm

Closed on national holidays

Entrance: 1 euro (free entrance for students)

Telephone: +357 243422648

Bee & Embroidery Museum (or what the Queen said «no» to)

This 1912 private house is situated in the middle of a small courtyard and is surrounded by old buildings. It still belongs to the same family, whose forefather was Kiriyakos Tsamilies. His heiress (his great-granddaughter) is the current head of the museum — Ellie Cornitou. We ran into her completely by accident during our visit to the museum. We were very lucky because we got a chance to chat with Ms. Ellie herself.

One of the outside buildings houses an exhibition dedicated to bees and honey. We discovered the history and the production process of honey and learned interesting facts, such as that bees seal the honeycombs when they are full and that in order to unseal them the beekeeper needs to cut the top layer of wax and then place the honeycomb inside a centrifuge machine that extracts honey. The wax can later be used in cosmetics, the food industry or to make candles.

The exhibition also includes different tools and a beekeeper’s suit.

Ellie: This house is about 300 years old. It was restored to its original shape and looks exactly as it did years ago thanks to a grant that we received from Europe.

I am going to tell you a few things about honeymaking and apiaries. Many years ago people used to keep bees inside ceramic beehives and the honeycombs were round in shape. The honey used to be extracted by hand. Today the beehives are made of wood and the beekeeper fills them with rectangular frames on which bees build their honey. This centrifugal machine can yield more than 100 kilograms of honey. Did you know that the queen bee (the mother of most of the bees in the beehive) can grow up to 2.5 centimeters in size and lives approximately 8 years? The others are either drones (male bees that never work and only mate) and worker bees (that work all their life) that live between 45-50 days. Each season used to yield about 10-20 kilos of honey. By the way, one frame must be kept with honey intact so that bees can feed off of it until the next bloom period. Eighty percent of Cyprus flowers are suitable to making honey.

Bees continue to work even in the winter, but instead of leaving the beehive they stay inside. We don’t harvest honey in the winter — because it is needed to feed the bees.

— What if the winter was too harsh and there isn’t enough sun in the spring?

— Well in that case the «winter period» is slightly longer.

There are large clay pitchers filled with wine in the courtyard. The label claims it was harvested in 1954. There is also a moonshine still that once again reflects the love for Zivania in this country.

We enter a nearby barn.

Ellie: The ceiling was made of vines and we have kept it this way to make sure it looks the way it did 300 years ago. All of the objects (tools and accessories) that you see here — harrows, sickles, sieves, harnesses — all this was used in the field and in the garden. And here is a type of washing machine!

— Ms. Ellie, who was responsible for making all these tools and objects? Were the peasants skilled enough for that or was everything made by special craftsmen?

— Most of the tools were obviously created by professionals. But sometimes people were able to get by on their own for the sake of economy. Actually, each village was famous for its type of shop (usually only one) and people would travel to different villages to buy a certain tool or material. Just like with most crafts, almost everyone knew «how it’s made», but few were skilled enough to do it. Plus, you have to keep in mind that farmers have very little free time.

At the same time, everyone was taught to respect other people’s work since they were little.

We are invited to visit the next room, which turns out to be the kitchen.

Ellie: This space is all about cooking and making bread. Here is a prototype of a refrigerator [looks like a pantry — ed.]. The baskets that hang from the ceiling were used to store food and protect it from pests and pets. Bread kept in these baskets could stay fresh for up to a week. But even dry bread was never thrown away and was instead used in cooking. Cheese (khallumi and anari) was made here as well using a large bowl and wooden trays. The baskets were used to store the cheese. Actually, many of the objects on display used to belong to my mother-in-law, who in turn inherited them from her ancestors. Life used to be much easier back then and people didn’t know anything about financial crises.

— Is Kato Drys cuisine different from that in Lefkara? Take, for example, the famous tavas [lamb with rice and vegetables, cooked in a pot — ed.].

— Generally speaking, yes. Our version of tavos is different and is even called «katodritikos tavas». Do you want to know our secret? We use goat meat instead of lamb, so it’s not too heavy. Also, I remove all of the fatty pieces from the meat and instead add olive oil — this way it’s much healthier.

We asked Ellie to tell us about the fox that we saw on that sign on main street.

— Where does this image come from? Is there a legend behind it?

— There is actually one old legend behind it. Every village has something of that kind. According to this legend, residents of Kato Drys once came to Lefkara and saw a church that was painted white and beautifully decorated. They asked Lefkarians: how did you manage to build something so beautiful? They started joking: we used yogurt to paint the walls. When the residents of Kato Drys went back to their village, they decided to do the same and brought buckets of yogurt to the church and «painted» it white. A bunch of foxes came in the night and licked off all of the yogurt. It’s an old joke, but there is a shred of truth to it: it was important to the locals to stay ahead of the competition or at least not to fall behind.

We have a good relationship with Britain (particularly as part of Erasmus+ educational projects). There is a British artist, who now lives in Lefkara and frequently visits our village. He offered to make this sign in order to reflect this historic moment. So in the end we did manage to beat our neighbour in some ways! (Ellie laughs)

We go up to the top floor of the house and enter traditional residential quarters — a living room and a bedroom. The window shutters are closed in order to protect the numerous artifacts from the sun. Some of the objects on display (such as handcrafted knickknacks, lacework, embroidery, bed linens, etc.) are almost 100 years old. The furniture is mostly made of carved wood. There is a weaver’s loom, behind which the woman in the house spent much of her time.

Ellie: This type of carved beds were a common form of dowry. They were quite expensive. Meanwhile, families usually had more than one daughter. My grandfather was not an expert in these things and used their bed as building material. These are carved chests — as you can see, people didn’t have much furniture back then. Even the weaving loom is made of carved wood to make it look beautiful, since a woman could spend hours behind it. There was another reason why women spent so much time doing housework — it was frowned upon for them to leave their house without a specific purpose.

We enter another, newer part of the house that includes the parents’ bedroom with private access to the garden, second bedroom and children’s room — all of them are dedicated to the art of lefkara lace.

You can tell from the atmosphere, that the house used to belong to a wealthy family. You can also easily feel the spirit of the time period. There are early 20th century photographs hanging on the wall (Ellie points out her mother on her wedding day), wedding gifts are displayed on the shelves of a cabinet: a silver tray and Lefkara pomegranates; wedding wreaths are kept in a frame.

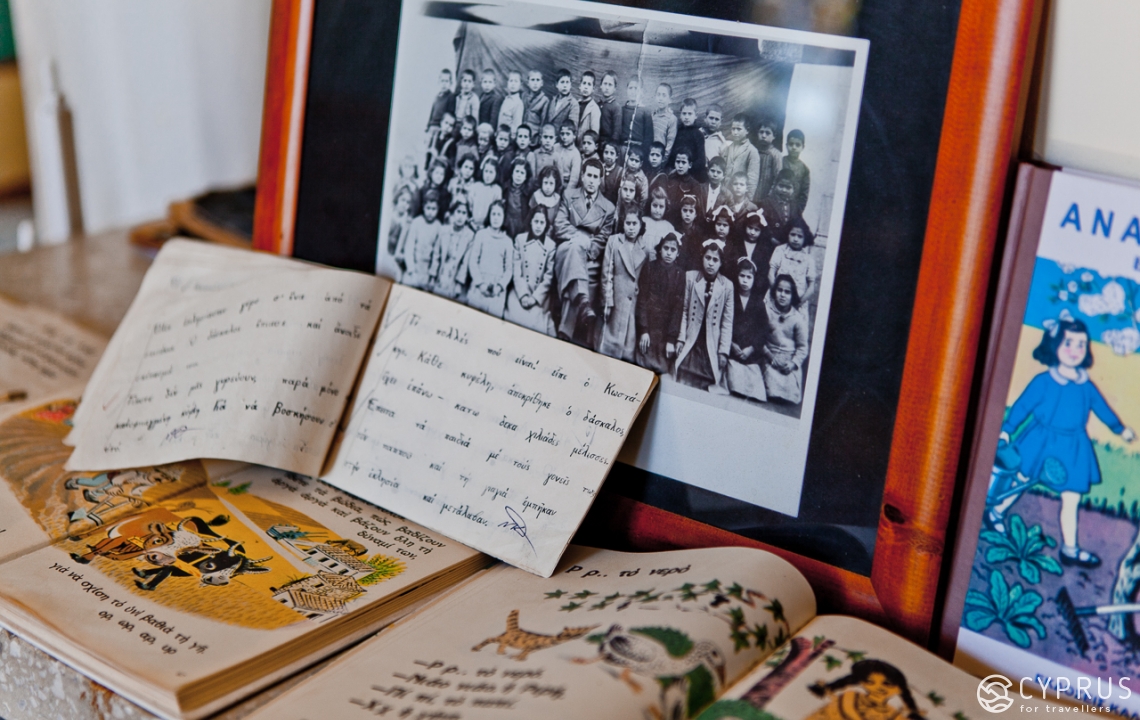

Ellie: This is a typical 1937 home. You can tell that it’s different from the older house. This is a photograph of my mom on her wedding day. It was the first time that a photographer from Larnaca was invited to a wedding. He took three photographs over the course of three days: one outside the church just after the ceremony, another photograph was taken near the house and the last one is that of Kato Drys. These are my great-grandparents, who were the first people to leave Cyprus to sell lefkara lace. They were pretty successful, which is how they were able to build a house such as this one. They also helped to build two village schools: one for boys and one for girls. Here is a written record of their sponsorship, which also mentions the presence of British authorities and the Bishop of Larnaca at the grand opening. My grandfather Michalis also donated money for the construction of the church of Agios Georgios in 1947.

— So it wasn’t just the Lefkarians who were involved in handicraft commerce?

— They were the trailblazers that paved the way for other villagers. Lefkara lace was and is produced all over the Lefkara region, including the village of Kofinou and Kato Drys. The local tradition of lacework emerged in the 12th century, but with the arrival of the Venetians in the 15th century it also incorporated Italian practices.

Being a trailblazer and starting your own business is always quite difficult. You had to look good, plus you had to find wealthy clients, since handmade lace was quite expensive. It was common for young people (15-16 years of age) to leave their country in search of customers. It was illegal, but the local mayor and priest would help falsify their papers.

— Ms. Ellie, can you tell us about the incident that took place between Kato Drys and the Queen of England?

— There was more than one. Here is an interesting story. Our fellow villager, Argiros Stakis, arrived in London when he was a young man, and came across the Royal Palace. He thought it was just a home that belonged to a wealthy family and decided to try selling lefkara lace to its owners. Surprisingly, he was invited inside and asked to show his goods. He ended up selling some lefkara lace for the Queen herself and received a check in return, which he never cashed keeping it as a memory instead. Unfortunately, the check was eventually lost. His relatives now live in Limassol. We asked them to donate a photo of the check to our museum, but they are still trying to locate it.

Now here is a bedcover: this needlework took me and my grandmother three years to create. You want to know what this pattern is called? Actually my grandmother came up with it on her own. Even when the seamstress used a traditional technique, she would often introduce something of her own. Plus, my grandmother was a very talented and creative woman. She was a gifted seamstress starting from an early age. Over the course of her life she managed to create 67 wedding dresses. It’s not that easy! And she liked to add her own designs and ideas to them — something that came to be in demand with the export of lefkaritika.

— Here’s another story about the Queen. This is a photograph of my mother-in-law, her daughter and her sister embroidering a tablecloth that was meant as a gift for the Queen’s coronation ceremony in 1953. The tablecloth was paid for by a group of Cypriot merchants that intended to present it to the Queen. But the timing was very bad and the gift was doomed. You see, two years prior to the coronation Cypriot rebels had assassinated a British ambassador. So when the merchants sent the Queen a photograph of the women working on the tablecloth, she responded with a refusal to accept it.

— I just noticed something interesting. One of the seamstresses looks exactly like the Queen herself. Do you see it?

— You are not the first person to say that. This is my husband’s wife. She still lives in Kato Drys. And she really did look like Queen Elizabeth's twin sister when she was young. British tourists tend to be particularly taken aback by this photograph picturing their queen working alongside Cypriot seamstresses. (Ms. Ellie laughs) So that’s another «royal» story for you.

We enter the next hall — a room with hand forged metal furniture brought from England. This is where older sisters would work on new tablecloths and other fabrics. Finally, at the end of this succession of rooms there is a children’s room — a small, but sunlit space with a terrace. Nowadays it is home to a souvenir shop, where you can purchase different knick knacks and things like sachets and purses (70 euros), napkins (40 euros) and porcelain dolls dressed in traditional Cypriot clothes (38 euros) — all of these objects have been decorated with traditional handmade embroidery. You can also have something custom made just for you.

— There is something else I’d like to ask you: the wall decor seems so unusual for Cyprus, so «royal». Is that European influence?

— This choice of color was borrowed from Italy. There is some British influence here as well. It is everything that people saw when they visited their clients’ homes.

We go out to the terrace to admire the vineyards before leaving the Museum and our hostess. But it turned out that this was still not the end of the exhibition. There was an enlarged piece of embroidery pictured on one of the walls. This is when I remembered about the Erasmus+ educational programs and a group of student artists from Slovenia, who recently took part in it. Major media outlets in Cyprus covered this event. It turned out that this wall, in addition to a few other walls around Kato Drys, was in fact their creation.

Ellie: Do you know what this image is about? It is a stylized figure of a woman borrowed from traditional Greek embroidery. It refers to the tragic moment in history, when Turks arrived in Greece. Back in 1803 the usurpers had surrounded a monastery next to the mountains of Zalongo. A small group of women and their children, who ended up trapped by the troops, decided to commit mass suicide rather than be enslaved by the enemy. They first threw their children down the cliff and then jumped down the precipice one after the other while singing and dancing. This print, called the «Zalongo dance» was created in their memory. A similar story took place in Cyprus, when a group of Turks came to the island and rounded up the women in Famagusta and put them on a boat to be shipped out. One courageous woman named Maria snuck into the ship’s hold and set off a bomb, killing everyone including herself and sinking it.

We thanked Ms. Cornitou for a fascinating journey into the history of Kato Drys.

Museum hours

Winter: everyday, except Thursday: 10:00 – 13:00 and 14:00 – 16:00;

Summer:everyday, except Thursday: 10:00 – 13:00 and 14:00 – 18:00

Group tours must be arranged beforehand.

Telephone: +357 99892677, 357 99419491 (Theodora Cornitou)

Entrance: 2 euros

Miscellaneous facts

Kato Drys is pictured on one of the Cypriot bank notes. In fact, one can easily make out the «Bees & Embroidery» Museum in the image.

The village is the birthplace of St. Neophytos (born 1134). His home still survives and there is a small church dedicated to him. A legend claims that his parents were too poor to give their son education and he was forced into marriage at the age of 17. The young man chose to become a monk instead and joined the St. Chrysostomos Monastery and later made pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Afterwards he carved out a home for himself inside a cave near Paphos, where he spent the rest of his life as a hermit. St. Neophytos is celebrated on September 28 and January 24.

Kato Drys is also the birthplace of Sir Reo (Argiros) Stakis (1913-2001), the owner of Stakis Hotels. He began his career as an entrepreneur as a lefkara merchant and has always been a supporter of his home village (e.g. introduced a plumbing system, created 15 thousand jobs in England for Cypriots, established the «Stakio» medical center).

Lodging and eating

At the end of our tour we found ourselves deciding on the best place to eat and rest. What we came across inside Kato Drys had already closed for the day and we ended up at the Platanos tavern just outside the village. It is a popular place among the locals and agricultural tourists. It is known for the huge sycamore tree, whose crown hangs over the tavern and the surrounding square like a canopy. The light bulbs that hang on its branches light up the tree in the evening and create an especially magical atmosphere. The tavern serves lunch and dinner. Prices range between 8-12 euros for a dish and 2.5-4 euros for a drink.

Telephone: +367 24342160, 357 99688761

If you decide to spend a couple of days in Kato Drys, then here is a few places to keep in mind:

Blue Oak Hotel: has 4 air-conditioned rooms with balconies and a kitchen. Showers are equipped with blow dryers.

Contact information: + 357 99680556, blueoakhouse@gmail.com.

The Carnitou Family (the owners of the «Bee & Embroidery» Museum) offer rooms inside a traditional house with authentic Cypriot furniture.

Contact information: +357 99892677, 357 99419491 (Theodora Carnitou), larnaca.rentals@gmail.com.

Palatakia Cyprus Village Houses has rooms and studios inside traditional houses. Guest are served breakfast. There are two swimming pools, television and a bar.

Contact information: +357 99934807, info@palatakia.com.

Website: www.palatakia.com.

Events and other things to see

Kato Drys frequently holds different educational and cultural events. To learn more about what is coming up, please visit the village’s website (at the end of the article), call: 357 24342833, 357 99676685 or email: symvoulio.katodrys@cytanet.com.cy.

Kato Drys churches

The largest one is the Church of Agios Haralambos, which was built in 1897 in honor of the village’s patron. The church can accommodate up to 150 visitors. The northwestern part of the village is home to Panagia Eleousa — the oldest church in Kato Drys, which dates back to the 12th century. Its recently renovated interior features two antique icons of the Virgin. Nearby is the Church of Agios Georgios — the «newest» church in the village (built in 1948).

The Church of Agios Neophytos

There is a small, single-nave church in the southwest of the village that sits atop the slope of a mountain. This church is dedicated to St. Neophytos. It was built in 1923 with donations from the local residents. Another village resident, Anna Pattahi, has financed its recent renovation and maintenance.

Getting there:

From Nicosia (50 minutes) and Limassol: take Route A1 (Nicosia – Limassol) until the exit for Skarinou, then head towards Pano Lefkara – Kato Drys – Vavla until you hit the sign for Kato Drys.

From Paphos (2 hours): take Route A6 heading to Limassol then follow the directions above.

From Larnaca (35-50 minutes): take Route B6 (Faneromeni street) towards Limassol, passing the Kalo Chorio intersection. Then take Route A5, then A1 until the exit for Skarinou. Then follow the directions above.

Parking: there are two parking lots on the right side of the main street shortly after you enter the village.

Buses: www.osel.com.cy, www.cyprusbybus.com

This is our first stop in this region and we have already managed to fall in love with it. We will come back here soon with a story about Vavla — its people and history.

Read more: www.katodrys.org

Enjoy your trip and see you soon!